A magician shows you the bottom of a deck of cards, letting you see the queen of hearts. They rub their hand over it, obscuring the card for barely a second. Suddenly, an entirely different card sits there.

How did that card change? Logically, we know it must be sleight of hand. So how does the magician convince you of this so-called magic?

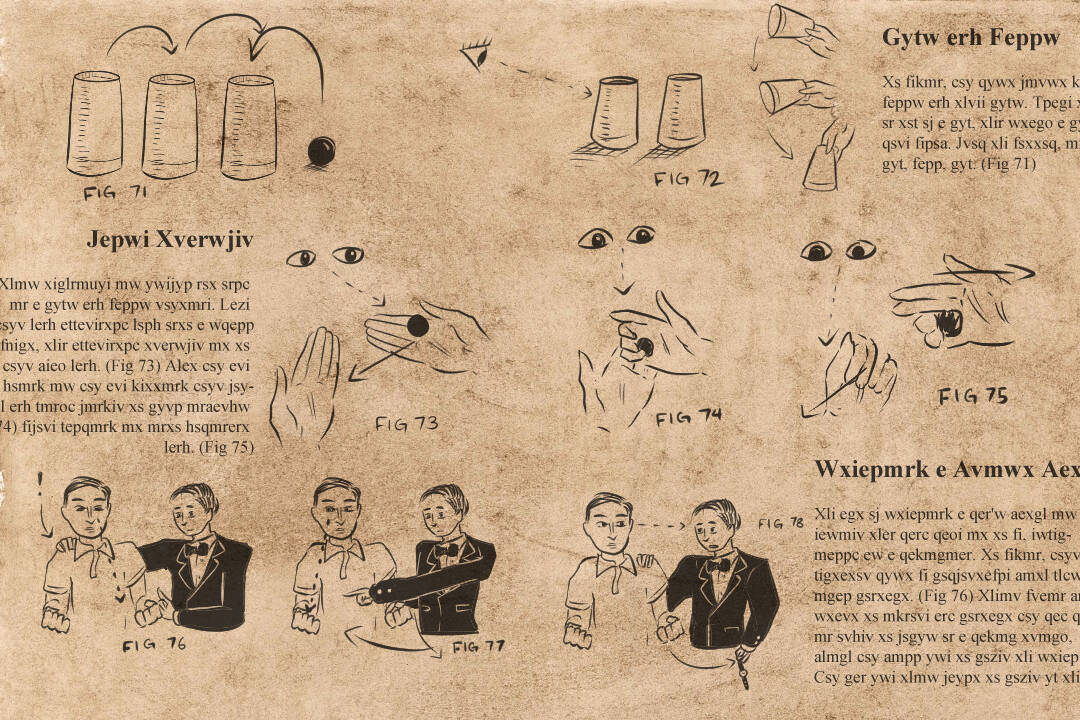

Human perception is incredibly fallible, and this becomes far more noticeable when magicians exploit it for the sake of entertainment. One such example is our limited perception of contrast. That limitation allows magicians to hide dark objects against a dark background, making them virtually invisible to audiences until they are presented with a flourish, as if they appeared out of thin air.

Magicians are also great at providing you with the illusion of free will, even when every choice you make is in their hands. In card magic, for example, magicians may ensure you choose a specific card while letting you believe that it is chosen of your own volition. In order to figure out the trick, your mind will stay alert and will focus on every movement the magician makes once they take your card back — while being completely unaware that the sleight is already done.

Even in cases where the magician does not force cards on you, your prior biases may make tricks much easier for the magician. Researchers from McGill University, Kwantlen Polytechnic University, and the University of British Columbia carried out studies showing that when a magician asked an audience to pick a card, only four cards account for over half of all audience choices. About a quarter of all participants chose the ace of spades, followed by approximately 14 per cent that chose the queen of hearts, and around six per cent each that chose the ace and king of hearts.

Magic tricks are often great studies in exploiting and modifying memory. It is surprisingly easy to convince someone they had chosen a specific set of cards when they chose an entirely different one at the start of the trick.

So why does any of this even happen?

One explanation for this phenomenon, which Professor Dirk Bernhardt-Walther explores in his course PSY198 — The Psychology of Magic, is that the brain is always looking for the most efficient way to solve a perceived problem. Neural processing attempts to be a highly optimized task — our brains try to use the least amount of time and energy to make conclusions.

And while this sort of processing has been imperative to our success as a species, it can be a detriment when understanding magic. Magicians use this fact to their advantage, allowing the brain to make quick conclusions and subverting expectations to trick the spectator.

Another possible explanation of this phenomenon could come from the top-down conception of perception and processing. You may be familiar with the bottom-up processing method, where we process sensory information as it comes into our brain. If you show someone a picture, their eyes will look over it, relay that information to the brain, and then the brain will tell you what that picture is. This processing builds bits of sensory information into a whole picture.

Intuitively, bottom-up processing seems to make sense, but top-down processing suggests that cognition also drives perception. Your brain relies on experience and knowledge and applies this to sensory information coming in, making you more likely to perceive things that you expect. A popular example of this is viral social media clips where the same audio plays on a loop, but you can hear different words from it, depending on which words you read at the same time.

When you see magic tricks, your brain will already have a prediction of what will happen, and whatever you see will confirm that, even if your prediction is wrong. Unless the magician makes a mistake, they can easily exploit this prediction to carry out various sleights without you noticing anything.

Magic is a performance more than it is scientific sleight of hand, and performances are often what trick us. When I perform close-up magic, I keep talking during the performance, especially when I’m about to carry out a sleight. As soon as I speak to the spectator, they look up away from the cards to make direct eye contact. Even if they do so for just a fraction of a second, that can be enough time to throw off their attention and trick them.

The mechanics of most magic tricks are simple and have been relatively unchanged since their creation — what changes are the mediums and methods through which these tricks are presented.

Learning the mechanisms of these tricks does not ruin the magic at all. Understanding these mechanisms gives us a deeper appreciation of the performative aspects of magic and the incredible mastery it takes to fool large audiences so thoroughly.