There are good photos. There are bad photos. There are photos that take you back to a certain time and others that don’t catch your attention at all. Ones that are taken with meticulous, technical care and others quickly snapped on a whim. There are photos so widely shared, most people can instantly recognize them. On the other hand, there are some pictures that never see the light of day. The interesting thing is, the appeal of photos seems to go beyond any limits of age, culture, or language.

Under a bridge on the Seine in Paris, France. VURJEET MADAN/ THE VARSITY

Colourful skies. VURJEET MADAN/ THE VARSITY

The earliest evidence of human art is 40,000 years old. Contrastingly, the earliest evidence of human agriculture is 10,000 years old. American author Elizabeth Gilbert pointed to these numbers in her book Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear, to make an interesting — albeit somewhat dramatic — point: “Somewhere in our collective evolutionary story, we decided it was way more important to make attractive, superfluous items than it was to learn how to regularly feed ourselves.” In other words, it seems creativity is innately human. Our desire to replicate and interpret the world seems to be in our very nature.

In the digital age, capturing moments has become almost too easy. At the very sight of a pink sunset, a relative blowing their birthday candles, a restaurant meal waiting to be eaten, or a couple reuniting after months apart, we take out our phones. However frequently or infrequently you might engage in photo-taking, one thing seems clear: collectively, we love to freeze time. In fact, there seems to be excitement in the act of it — capturing a moment that would otherwise flit by, stopping time, and giving our future selves the permission to revisit this moment.

Celebratory cake. VURJEET MADAN/ THE VARSITY

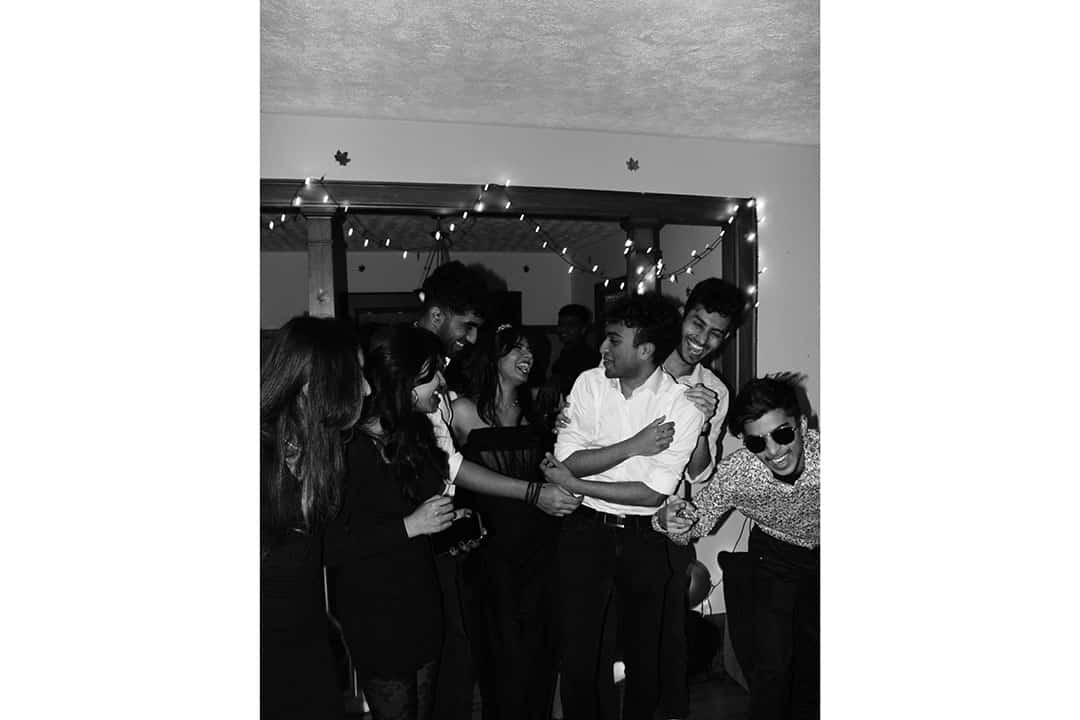

College kids in their college days. VURJEET MADAN/ THE VARSITY

The act of taking a photograph in itself seems too simple to really be considered art. You peer through a tiny window, you press a button, hear a shutter open and close, and it’s done. The artistry is arguably less so in the click of the button and more so in the knowledge of when to click it. What makes a moment capture worthy? Which moments do we deem valuable enough to hold as a memory?

On a road trip. VURJEET MADAN/ THE VARSITY

Sometimes, it is the story behind an image. Other times, it’s the time-travelling window it provides. Whether they be historic wartime images or pictures from your high school days, the past is brought to life in photographs. We become children; the photo, our wardrobe; and the memory, our Narnia — for a small moment, we are transported to a different world.

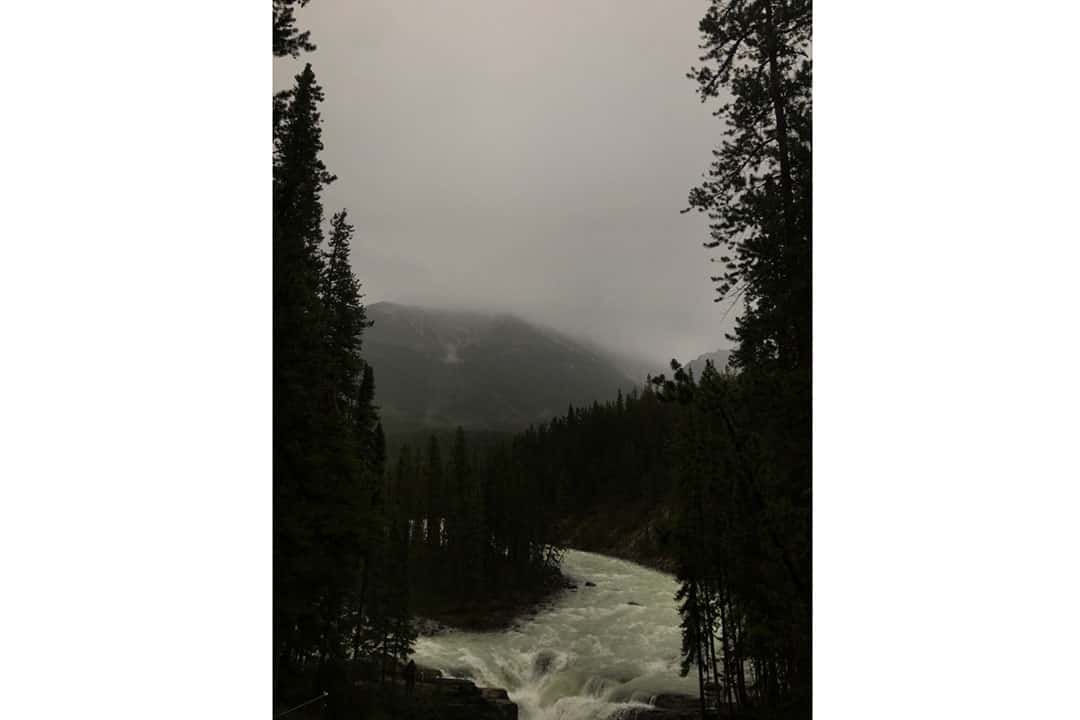

Nature’s beauty. VURJEET MADAN/ THE VARSITY

Portraits, in particular, capture human essence in a profound way. You see the person’s character. The creases and lines that decorate their face. Is there youthful energy in their eyes? Or years of memory and wisdom in them? Do they smile with conviction and confidence or with self-conscious timidness? In many ways, a photo allows you to capture someone in a way that language never could.

Bright sun rays hiding brighter smiles. VURJEET MADAN/ THE VARSITY

In a broader way, the act of image creation is an act of capturing the truth. In taking a photo, you create something that records life — that remembers life. It transcends the limitations of our own memory and provides us a less perishable version of it.

A road along Gerrard St West, Toronto. VURJEET MADAN/ THE VARSITY

Ultimately, we are survived by our photos. We capture life, and culture, and people, and things. Like Joanna Zylinksa proclaims in her study on photos and survival, After Extinction, photography is a quintessential practice of life. As bearers of the camera, we choose what is worth photographing: what is worth being remembered by and remembering by.

Passengers on a ferry, off the port of Dover. VURJEET MADAN/ THE VARSITY