Content warning: this article discusses instances of medical violence against Indigenous peoples.

From a history fraught with unethical medical experiments in residential schools — including government-funded research on malnourishment that withheld dental care and a 1955 case of the allegedly unnecessary removal of portion of a lung — and a wide range of ongoing health inequities, it is unsurprising to find medical reform among the Truth and Reconciliation Report’s Calls to Action (TRRCA).

In the health-related subsection of the Calls to Action, only one article explicitly pertains to the training of medical professionals themselves, asking that medical and nursing schools require students to complete a course on Indigenous health issues. The rest call for action from the federal government, seeking comprehensive health-care system change on all levels. These changes would include increasing the number of Indigenous professionals in health care, retaining health-care providers in Indigenous communities, and providing cultural competency training for all health-care professionals.

A lot has changed since that report came out in 2015.

Here’s what universities, medical schools, and medical professionals are doing to meet some of the health care-related calls to action — and how our health-care system still needs to change.

Laurentian University, Simon Fraser University, Lakehead University, the Northern Ontario School of Medicine (NOSM), and U of T have begun to offer graduate programs specific to the health needs and concerns of Indigenous and rural northern communities. The Temerty Faculty of Medicine at U of T offers a masters in Indigenous public health, has drafted plans to “recruit Indigenous faculty and staff to lead all aspects of Indigenous medical education,” and has instituted an Elder-in-Residence position. Today, this position is held by Elder Kawennanoron Cindy White, who also holds a degree in nursing.

Despite these advancements, there’s a long way to go. Indigenous peoples comprise five per cent of the Canadian population but only a little more than one percent of U of T’s medical faculty and, as of 2023, there are four faculty members who publicly identify as Indigenous: Dr. Chase McMurren, Dr. Jason Pennington, Dr. Lisa Richardson, and Dr. Suzanne Shoush.

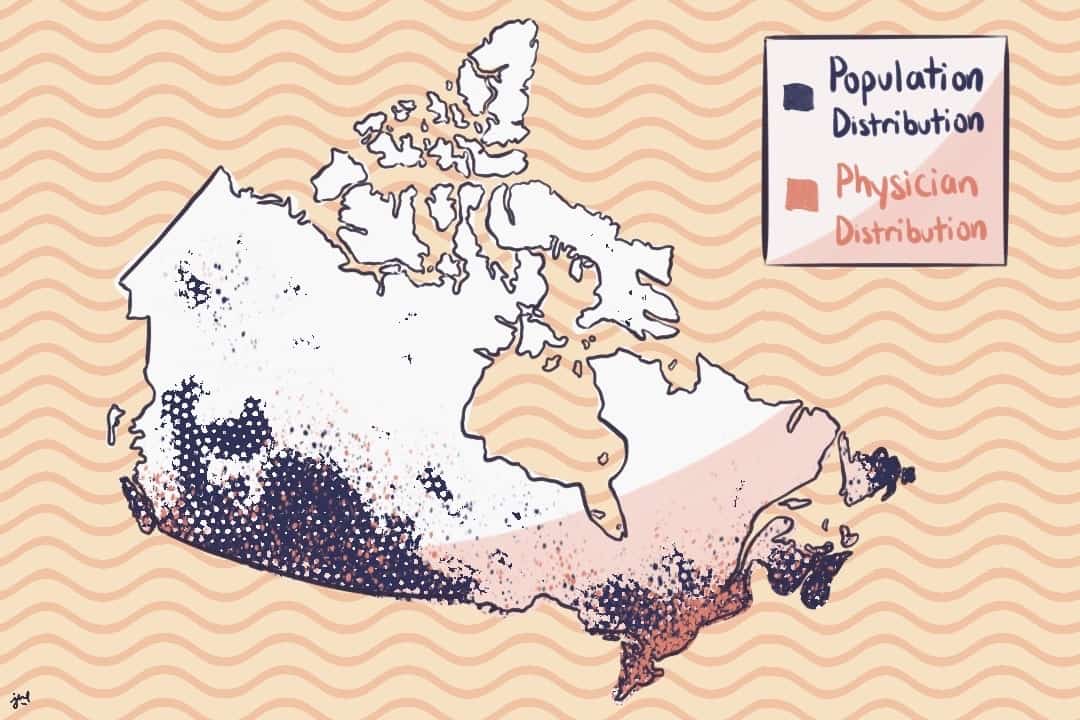

Although 33 per cent of the overall Canadian population lives in rural areas, for Indigenous peoples, that number is approximately 60 per cent. In contrast, a mere 9.4 per cent of all physicians are located in rural areas. This becomes an issue for Indigenous health care because low physician retention in northern regions leads to an issue in access.

Urban masters programs may not be enough to entice doctors further north; this is why NOSM was founded.

In 2002, Laurentian University and Lakehead University collaborated to found Canada’s first independent medical university, intended to prioritize medicine for rural northern communities, by northern communities. With campuses in Sudbury and Thunder Bay, NOSM aims to take learners “out of the ‘ivory tower’ and into [the] backyard” and fill the gaps in northern rural, Indigenous, and francophone medicine. Among its medical programs, NOSM offers the Remote First Nation Stream, a rural residency program that involves community immersement in the Eabametoong First Nation.

Less than a quarter of NOSM graduates stay in rural communities in northern Ontario, but NOSM reports that more than half its graduates stay in northern Ontario cities, and nearly eight per cent of all its medical school graduates are Indigenous.

This trend is positive but does not combat the lack of access to specialists, and many still travel long distances to attend appointments.

“My mom has a disability,” fifth-year U of T global health specialist Madeleine Leach Jarrett told The Varsity. “I grew up — my whole life, as a little kid — going to hospital and doctor’s visits and stuff with her… I’ve been kind of knowledgeable and understanding of the public health system and how it functions since I was young.”

From experiencing disparities in the northern public health system and studying them in school — in both her specialist and double minors in immunology and Indigenous studies — Jarrett is sympathetic to both the health professionals who cannot stay in the north and the patients who need them.

She believes in a different future of health care: “Instead of making people travel ridiculous distances, spend extreme amounts of money, drive on roads that are dangerous in the winter — all these different factors — we could be able to do some sort of telemedicine visit… there could also be an in-person component at a local clinic with a local doctor or nurse practitioner, and then an online component with a specialist.”

Jarrett is optimistic about the future of a hybrid model. “We just need to be both adaptive and creative in how we solve these things,” she said. “Now that we’ve gone through COVID, we’ve seen that we actually can be more accommodating with our systems. We can create accessible systems for everyone.”