The soldier stepped forward to block my path, one hand stretched out in front of me, the other on his assault rifle. First in Arabic, and then in English after my confused apology, he barked: “Where are you from?”

Canada.

That word was like magic in Jerusalem’s Old City, prompting softened looks from authority figures and almost, but not quite, removing their predisposed reaction to my hijab and ethnically ambiguous face.

“Canada! How are you?” His face and tone instantly became playful, perhaps betraying admiration for my citizenship, but he nonetheless checked my passport, and my sisters’ passports, before letting us pass.

In the five days I visited Jerusalem and the surrounding cities as I toured the Middle East with my family this winter, I became used to seeing guards holding assault rifles longer than my arm. The aura of power and fear that surrounded them marred the cobblestone streets and otherwise immaculate historical beauty of the region.

I became used to the soldiers who guard the Al-Aqsa Mosque — the journey to which is notoriously difficult no matter where you hail from — stopping me at the gates. I became used to pulling my Canadian passport out of my bag to confirm my citizenship and reciting verses from the Quran to confirm my religion — which also served as a passport in this highly controlled region.

As a tourist, I witnessed and experienced just an iota of the discrimination that the Palestinian people experience every day.

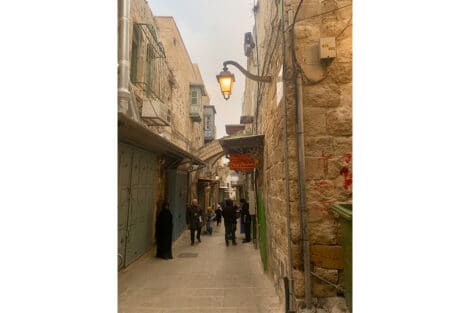

The stone alleyways are colourful and lively, but tainted by an eerie foreboding. SAFIYA PATEL/ THE VARSITY

I became used to not talking to — or looking at — strangers, and walking straight ahead with my head down, but not so low that I would bump into someone. The city was bustling, but tourists did not mingle nor loiter, anywhere, especially not near the soldiers’ many stations.

They walked the streets of the Old City and around the Al-Aqsa compound, their army green ironically standing out among civilians and tourists.

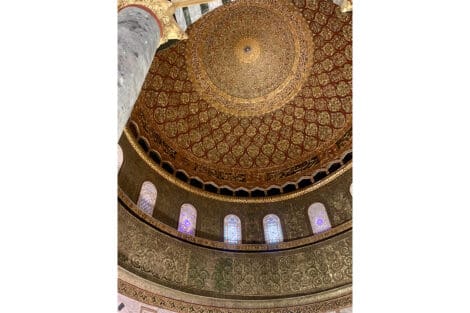

The Dome of the Rock is over 1,000 years old. Its dazzling artwork boasts designs from Late Antiquity and religious Islamic inscriptions. SAFIYA PATEL/ THE VARSITY

The Dome of the Rock in the Al-Aqsa compound has the most beautiful architectural design I have ever seen. The camera could not do the intricacies of the gilded designs justice. But only a select few people can experience this beauty.

Only those who identify as Muslim are permitted to enter the mosques within the Al-Aqsa compound to perform prayers. Non-Muslim tourists can tour the outdoor areas at certain hours. As I was walking out of the Dome of the Rock, my sister and I overheard a Christian woman complain about this — the compound holds religious significance for her too. Jerusalem is home to a variety of relics and sites that are significant for all three Abrahamic faiths.

In 1969, when tourists were permitted to enter the mosques, a religious extremist from Australia committed arson in the Al-Aqsa Mosque, resulting in extensive damage and heated demonstrations. Some of the most revered and historic parts of the mosque were burnt, including a 900-year-old pulpit, which was a gift from the Egyptian Sultan Salah al-Din Ayyubi, who captured the city of Jerusalem from the Crusaders in 1187.

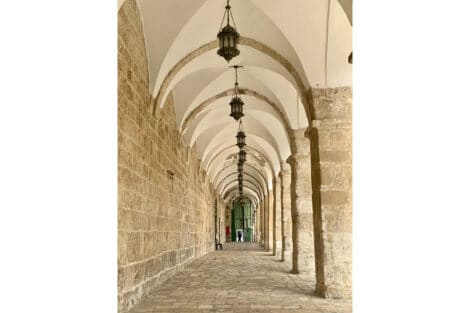

Al-Aqsa is beautiful, but often remains empty. SAFIYA PATEL/ THE VARSITY

The Al-Aqsa compound at sunrise, overlooking the Old City. SAFIYA PATEL/ THE VARSITY

The compound is beautiful and serene, but silence — emptiness — punctuates this serenity. Outside of visiting hours, only gun-toting soldiers and a few worshippers haunt the cobblestone complex.

Shops in the Old City, before opening hours. SAFIYA PATEL/ THE VARSITY

Walking through the streets of the Old City was like being transported back in time, thousands of years ago. The city has a special magic, as if covered in a golden glow. Even amid the chaos and fear, the shopkeepers were all so gracious, asking my sisters and I questions about ourselves as if we were the most interesting people they had ever met.

Walking by merchants and their shops was like walking through the pages of One Thousand and One Nights. SAFIYA PATEL/ THE VARSITY

Their faces lit up when we walked in. One shopkeeper offered discounts on anything we would glance at. His shop was too close to where the soldiers were stationed, he said. Tourists were wary of the proximity. He could go days without a single customer.

Bethlehem’s Separation Wall is a tangible symbol of apartheid.

SAFIYA PATEL/ THE VARSITY

The West Bank barrier that passes through Bethlehem isolates the Palestinian territories from Israel. The Israeli government started its construction in 2002 during the Second Intifada, a time of Palestinian uprising. The harsh grey cement has since become a museum of sorts for Palestinians, a canvas for their feelings — the graffiti a symbol of defiance against the separation, against the settler colonies on the other side.

There are posters on the wall with anecdotes and quotes from Palestinian people. “Dreams are for kids and for the stupid,” one poster reads. “We dream but we don’t believe it.”

The buildings of Hebron reveal remnants of beauty and strength. SAFIYA PATEL/ THE VARSITY

Hebron is home to many historic and religious sites — as well as many checkpoints, guarded by soldiers. These historic sites were once teeming with life, with residents selling their wares, but most of the stores have been shut down. The cobblestone alleyways are ghost towns. Few shops remain open.

They used to be doctors, scientists, professors, one of the shopkeepers told me. Now, those whose shops have been shut down live off charity. The few who are still working make few sales, as few tourists feel comfortable visiting due to the precarity and constant violence in Hebron.

Venturing into Hebron requires courage from tourists. Its residents cannot venture out without a visa.

SAFIYA PATEL/ THE VARSITY

I only visited Palestine for five days. Yes, I got used to keeping my head down, and I came inches close to so many rifles that I became an expert at contorting my body to avoid touching them. But every time a soldier stopped me or my hijab received a dirty look, I knew that this was temporary. I could pull out my passport. I could leave the country just as I entered it. I could come home.

But for Palestinians, that is home. A home some cannot leave without a visa. A home some were expelled from and can never return to. A home whose name is taboo, erased from maps.

Home is where the heart is, they say. But for some, the heart is the only safe place for the home.