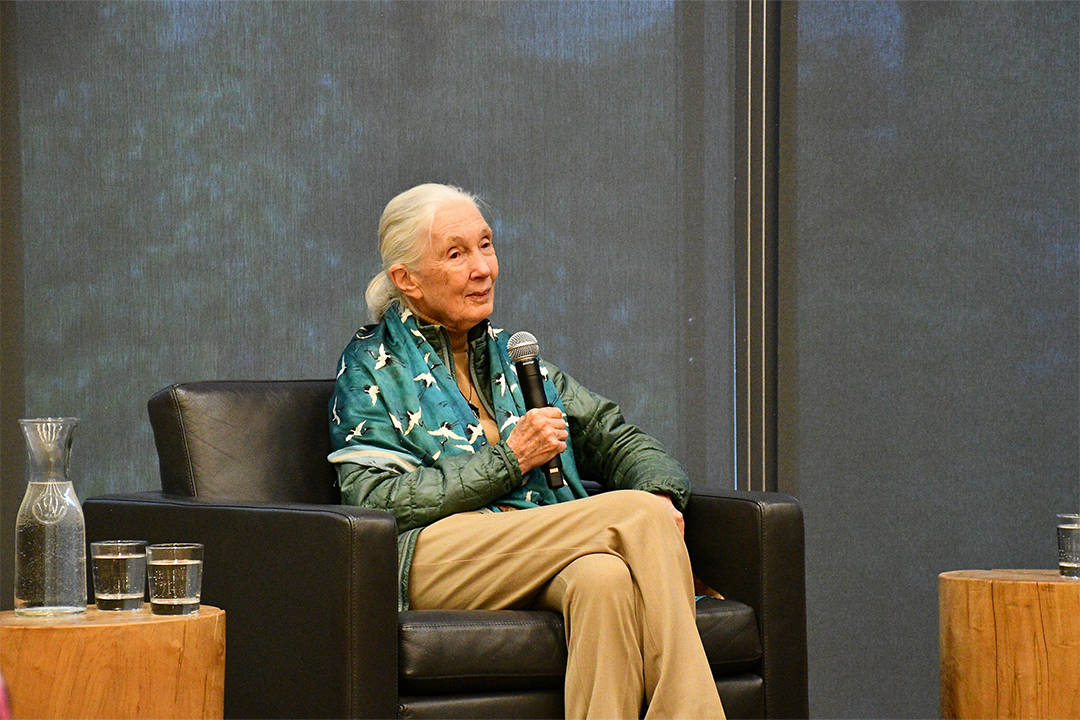

When Jane Goodall walks into a room, a series of unexpected things begins to unravel.

First, you realize that the 89-year-old iconic English anthropologist is of short stature — but also of an immensely powerful and dominating presence that stands taller than anyone else in the room.

Second, she carries along with her a bundle of soft, plush toy animals that have grown in size over time and her travels. To everyone’s amusement, she frequently mentions the toy animals — rat, monkey, and cow — and she refers to them all with endearing names.

Third, she greets her audience with chimpanzee sounds. As the short crescendo of her chimpanzee hoots echo across the audience — in sharp couplets of “woo”s and “ah”s — I am reminded that I am in the presence of a woman who has been making her mark in the world of both humans and animals much before I was born and continues to do so today.

Seeing such a seminal figure on October 13 inside the Desautels Hall of the Rotman School of Management was like seeing a storybook character come to life. I am being far from hyperbolic, as my first exposure to Goodall was quite literally through a Korean picture book with colourful drawings of her hugging chimpanzees.

At a young age, all I could gather was that Goodall had a respectable level of tolerance and kindness toward animals that inclined them to trust her, while I could barely coax a friend’s dog to look at me. At a relatively older age, however, hearing her talk at an event organized by U of T’s School of the Environment was illuminating — both in understanding her work and her as a person.

Goodall shared her lifelong journey from when she was a little girl to her first time setting foot in Africa, meeting paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, becoming cognizant of chimpanzees’ behavioural resemblance to humans, and discovering the need for nature conservation. With someone whose work has been globally renowned for as many decades as Goodall, you might expect a conversation about them to be full of “I”s and “me”s. Throughout the talk, however, Goodall rarely attributed her academic and social accomplishments to herself.

She attributed her initial fascination with animals and wildlife as a child to her mother — whom Goodall praised endlessly for her patience, understanding, and excitement toward her daughter’s curiosity. Goodall attributed her first step into the academic world of anthropology and paleontology, and her journey to the Olduvai Gorge in Serengeti, to Louis Leakey. Leakey later discovered fossil remains of the Australopithecus boisei — species with skulls adapted to heavy chewing — and Homo habilis — the most ancient representative of the human genus — in that area. Leakey also financially supported Goodall to pursue her PhD in ethology at Cambridge University, despite her not having an undergraduate degree.

Most importantly, Goodall attributed her lifelong scientific contributions to chimpanzees. She recalled the earlier stages of her career when older professors and scientists told her that she was doing “everything wrong” — from giving chimpanzees names rather than numbers to having empathy or believing that chimpanzees had personalities and emotions. Throughout the course of her research, Goodall has transformed the field so that we now know that humans are not the only sentient beings on Earth.

But Goodall claimed to have become an activist when she started to recognize the increasing loss of forest ecosystems and chimpanzee habitat. From this talking point, Goodall dedicated the rest of her talk to her efforts to protect our planet, chimpanzees, animals, and future human generations — mainly done through her organization Roots & Shoots. The organization began over 30 years ago and has since supported countless young activists to start their own projects and tackle biodiversity loss, climate change, and environmental inequity at a local level.

Given that the younger generation is most proactive in calling for political and social change to tackle the climate emergency, it is a refreshingly powerful change to see someone of a much older generation pave the way to help create a livable earth. We still need more people to “emerge as activist[s]” from being scientists, professors, lawyers, or doctors — just as Goodall did.

Reminiscing on the late 1980s, Goodall briefly discussed how many of the young university and high school students at the time were already losing hope in slowing down climate change. When Goodall asked them the reason behind the supposed apathy, the students had told her that the — now much older — previous generations had compromised their future, and there is nothing they can do about it. Goodall says, “We have been stealing our children’s future ever since the Industrial Revolution.”

Ironically, this was the most inspiring part of Goodall’s speech to me because it was a stark comparison between the previous generations and ours. Despite our planet being on the verge of what is reported as an irreversible climate breakdown, our generation isn’t losing hope. And with members of the older generation like Goodall, we can actually see the change that people like her have been working toward for decades. If anything, Goodall’s talk was emblematic of our generation’s hope and our unwillingness to let go of it. She is passing us the baton.

No comments to display.