Content warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of parasitic infection in humans.

In January 2021, a 64-year-old woman from Australia was admitted to her local hospital in south-eastern New South Wales with stomach pain, diarrhea, fever, and a dry cough. In 2022, she presented with neurological symptoms such as depression and forgetfulness, and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed abnormalities in her frontal lobe region. The hospital referred her to Canberra Hospital in Garran, Australia for a biopsy, which the doctors expected to indicate cancer or a buildup of pus in the brain.

None of these predictions were accurate, however. In June 2022, Dr. Hari Priya Bandi, the neurosurgeon who performed the biopsy, found an eight-centimetre red worm that was still moving upon extraction from the patient’s brain. It was an Ophidascaris robertsi, which could possibly have been alive inside her brain for up to two months.

This would be the first time that this species of roundworm was found in a human, as it is normally found in Australian snakes, specifically carpet pythons — but this definitely isn’t the first time a human has been infected by a parasite.

What are parasites?

Parasites are living organisms that depend on a host organism for survival. Humans can be infected with three types of parasites: protozoa, ectoparasites, and helminths. Protozoa are one-celled organisms that can multiply in a host. Ectoparasites are widely defined as organisms that consume human blood for survival, such as mosquitoes, and some latch onto skin for up to months at a time. Helminths, or ‘worms’ in Greek, are multicellular and large enough to be visible to humans when fully grown. These include flatworms, thorny head worms, and roundworms.

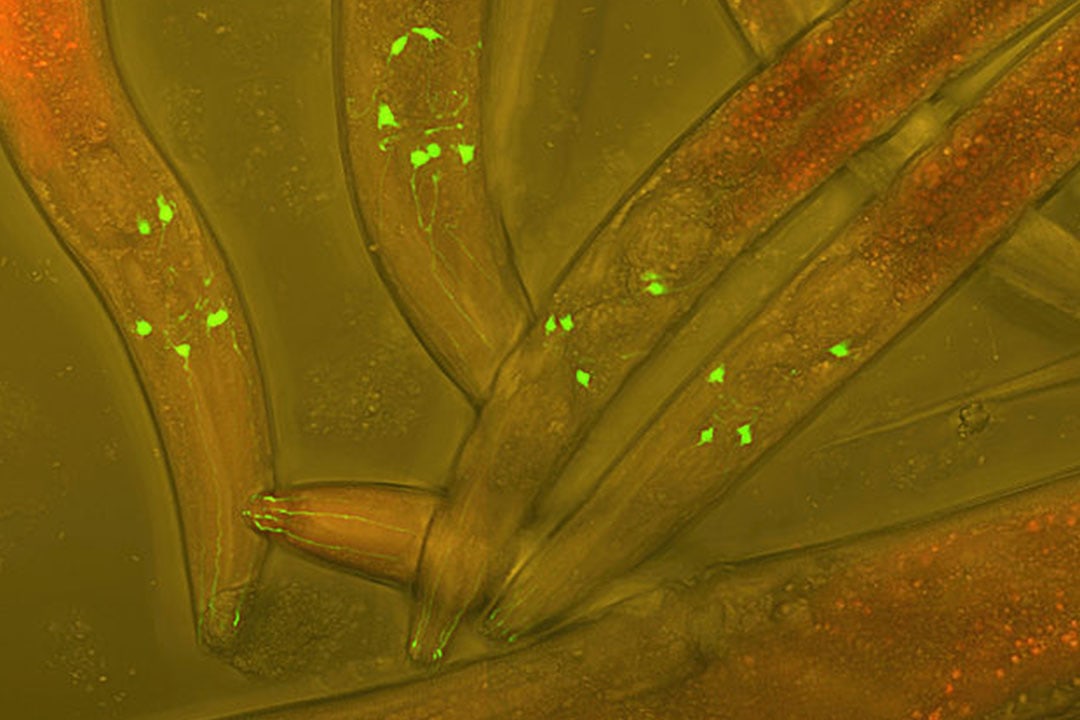

Roundworms are generally found in the gastrointestinal tract, the layer of tissue under the skin, the blood, or the lymphatic system. They often lead to stomach pain, diarrhea, fever, and dry cough — the exact symptoms the patient showed in 2021.

In their larval form, roundworms can also be found undeveloped and inactive in different tissues within the body. Dr. Sanjaya Senanayake, the infectious disease doctor working on the day of the discovery, told The Guardian that they treated the Australian patient for larvae that could have potentially found their way into other parts of her body.

Parasitic infections

While the discovery of Ophidascaris robertsi in a human was the first of its kind, a Global Burden of Disease study conducted in 2019 revealed that about 2.35 billion people had parasitic infections. At the same time, in 2019, the population was 7.7 billion — which means more than 30 per cent of the world was living with a parasitic infection. That year, parasites caused about 678,000 deaths, with over 58 million healthy years of life forfeited to parasitic infections.

One example of a parasite that can be found in the brain and spinal cord, as well as muscle, among other tissues, is a larval cyst of Taenia solium, or pork tapeworm. This type of parasite causes cysticercosis, a tissue infection responsible for seizures. Individuals are infected by consuming tapeworm eggs found in the feces of individuals with intestinal tapeworms, or consuming pork with larval tapeworm cysts. These eggs can be spread through contact, so if an infected individual doesn’t wash their hands after using the bathroom, they can spread the eggs through door knobs and other surfaces.

What does this mean for infectious diseases?

The question arises, how did this patient in Australia become infected with a tapeworm that has up to now been found exclusively in snakes? While she did not have direct contact with any snakes, she often picked wild grass to use in cooking. Scientists theorize that the worm came from an egg that was in the feces of a carpet python that contaminated the grass, infecting her brain upon consumption.

This form of infection could potentially be repeated, but it is highly unlikely. Zoonotic diseases, or animal-to-human transmitted diseases, are responsible for 75 per cent of new diseases found in patients globally. COVID-19 is an example. However, according to Dr. Senanayake in the interview with The Guardian, the transmission of Ophidascaris robertsi is not facilitated through human-to-human interactions and therefore unlikely to become a zoonotic disease turned global pandemic.

In December 2022, six months after the removal of the tapeworm, the patient’s neurological symptoms improved but had not been eliminated completely. She is still being observed. Ongoing research aims to determine if she has any underlying immune system problems that could have contributed to this infection.

No comments to display.