“Belief

Initiates and guides action —

Or it does nothing.”

Octavia Butler, born in Pasadena, California in 1947, was an African-American author who explored themes of climate change, Black injustice, and political imbalances through a feminist, dystopian lens. Butler’s celebrated trilogy Xenogenesis is set in a post-apocalyptic world, exploring identity, power, and race while navigating kinship within an alien race.

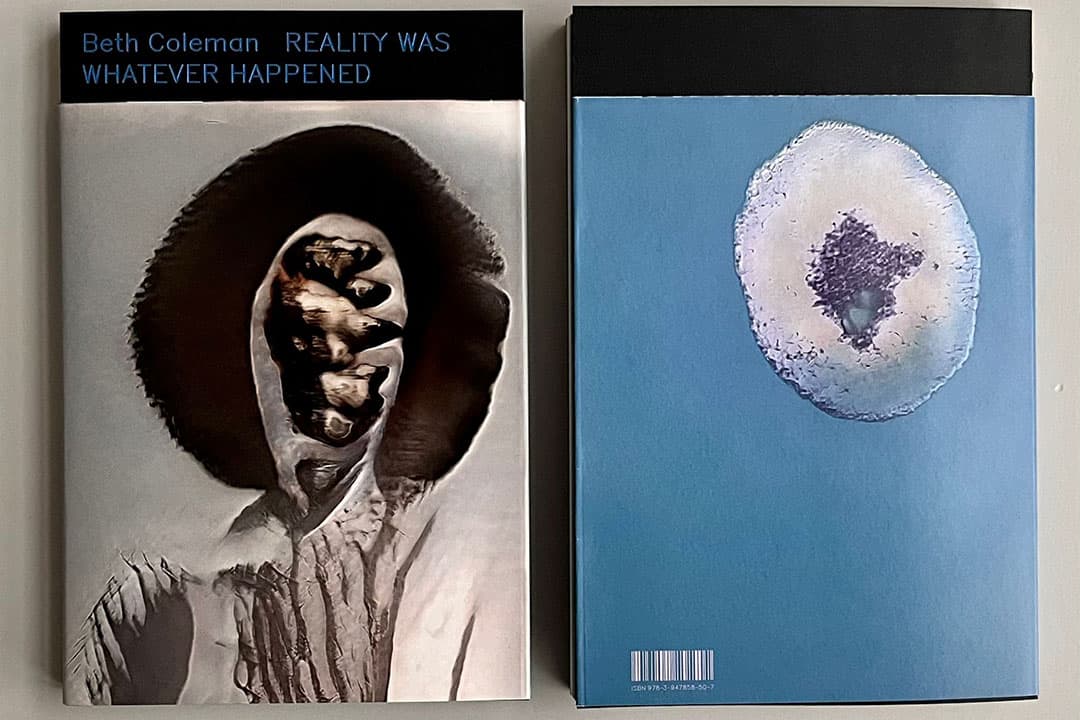

Beth Coleman is an artist and a professor at U of T who focuses on science, technology, aesthetics, machine learning, generative arts, and Black poesis. On November 2, Coleman held an event for the opening of her exhibition and the release of her book, “Reality was Whatever Happened: Octavia Butler AI & Other Possible Worlds,” at the Centre for Culture and Technology.

The exhibition and book are parts of Coleman’s AI-generated project, Octavia Butler AI (OBAI), based on the themes in Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis. Two of the event’s conversations were titled “The Liberation Project” and “With and Against.”

The Liberation Project

Concordia University Professor Alessandra Renzi, who studies the use of technology in research and activism, began “The Liberation Project” conversation with Coleman, who focuses on the intersection of politics and aesthetics. Renzi drew attention to conventional criticisms in artificial intelligence (AI), such as racial bias, questioning what can be done as a preventative measure against these biases. The OBAI project aims to radically transform our visual understanding of images, bodies, and worlds, pushing the boundaries of artistic creations with a critical lens of race.

Contemporary use of generative AI aligns with capitalist business models. Large tech companies have released large data sets of art for public use in tools such as DALL-E, which can create images from a series of text prompts. This can greatly exacerbate bias coming from the original art. This has been a topic of concern as Black artists have voiced that generative AI defaults to stereotypes and patterns that exist on the internet.

To better understand this, imagine if an AI tool is fed a data set containing 100 images of the Earth, 80 of which depict Earth as a square: the generative AI will predominantly create new images of the Earth as a square.

Some artists have begun to introduce anomalies, including deformities and irregularities into their artwork to prevent conventional categorization. As a result, generative AI that uses their art can curate distinct artwork that actually challenges traditional categories and aesthetics.

Generative AI has the potential to bring about exciting and liberating genres of art and contemporary ideas not tied to traditional elements and themes of art, but if misused, might instead deepen existing forms of oppression.

With and Against

Professor Michelle Murphy — who is Red River Metis from Winnipeg and a technoscience scholar at UTSG, with a focus on data politics, Indigenous science and technology, colonialism, and race — joined the “With and Against” conversation with Romi Morrison, a professor at UCLA, whose work engages arts, community, aesthetics, and land use practice.

Murphy made use of Butler’s words from her book Xenogenesis, comparing AI to aliens as “horror and beauty in rare combination.” Murphy says that humans might possibly collaborate with and against AI toward liberated futures. This liberation is not an inherent goal of AI, so how can artists manifest in generative art?

OBAI makes use of a generative adversarial network (GAN). GANs, invented by American computer scientist Ian Goodfellow in 2014, are a form of machine learning that uses two networks — one generative, creating new images, and another discriminatory, categorizing the real and generated images. The strengths of both networks can be modified to generate new images that are virtually indistinguishable from real ones.

Coleman initially fed a dataset containing afro-futuristic images to GAN, gradually using the technology to challenge boundaries of race and gender and create variation in the resulting artwork. Two of OBAI’s art pieces — “Alice,” a series of generative portraits blending Black femininity with a non-human form, and “BPP,” images inspired by the Black Panther Party, including concepts of landscapes and crowds — are manifestations of anti-oppressive generative art challenging what we know about portraits and landscapes through an afro-futurist lens.

Morrison brought in the idea that computational technology is unstable, as every input results in unique outcomes, which creates a strained relationship between AI and humans as we feel unable to predict AI-generated outcomes. The risk of AI tools learning entrenched histories of white supremacy, together with the current blurry boundaries and protocols of AI use, further strain that relationship.

The future of liberated generative AI then becomes contingent on the extent to which we can challenge and guide AI tools to work with and against itself to combat deeply ingrained issues of racism and colonialism we encounter in several forms of media. OBAI aims to foster this progress, at least in the realm of art.

No comments to display.