As my home country Egypt suffers one of the worst economic moments of its modern history, I find myself asking whether it’s relevant to have the same conversation I have every other Black History Month: to remind you that Black Egyptians exist. Who cares when we’re all suffering regardless of race, ethnicity, or religious affiliation?

Since the ongoing depreciation of the Egyptian pound that began in early 2023, the Egyptian economy has taken a major hit. Prior to the currency devaluation, 30 per cent of the country already lived under the poverty line, many of whom live in the southern parts of the country.

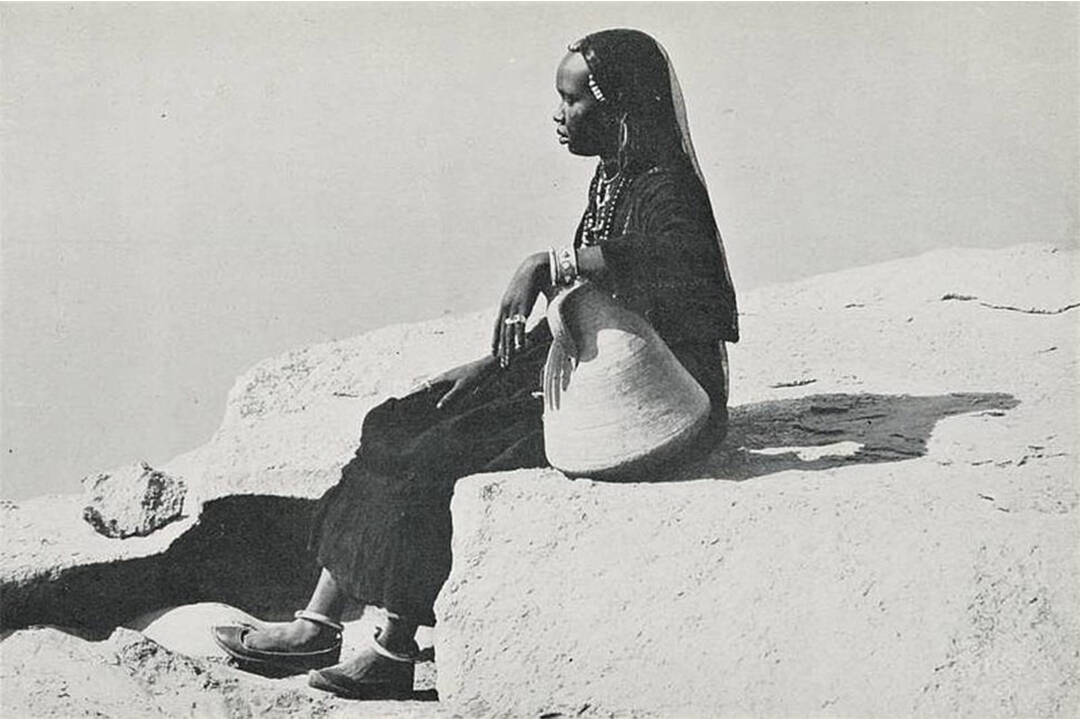

When I speak with my community members back in Aswan — the southernmost governorate of Egypt, which is home to many Black Egyptians — I realize just how bad it is. People I grew up with are forced to sell their jewellery and prized assets to make ends meet. Many I know have had to alter plans for their children’s education, and everyone I speak to is seriously considering immigration.

My childhood is marked by this unbelievable duality, one where I would travel between the metropolis of Cairo and the villages and townships of Aswan, seeing parts of Egypt that most Egyptians don’t even know exist. In my experience, the communities of Aswan live with poorer infrastructure, with few proper chances for education, and are often displaced by the state many times over: either directly, as in the case of our forced displacement to build the Aswan dam, or indirectly, where many of us had to migrate from areas like Aswan to Cairo for our mere survival. To be in Aswan means to be surrounded by resilient people, yes, but to be without basic necessities.

And then I would visit places like the North Coast, where rich Cairenes and all of the state’s beneficiaries have claimed ownership and treat it like some sort of Mediterranean playground. It always boggled my mind because this is the Egypt that they so heavily push in the media, while the other Egypt I know of is entirely omitted from the narrative.

I often think of how radically different my life could have been if my grandfather stayed in Aswan instead of migrating to Cairo. Would I have had the luxury of taking my sweet time to get through my degree while switching from major to major? Would I have even been financially capable of studying at a university, let alone a decent one? And now, as the country faces total economic collapse, I think of what price the people of Aswan have to pay that won’t be reported on and will be dismissed. Truthfully, the thought of that price scares me. And I find myself praying for all of us.

But we didn’t stay in Aswan. The fact that my words about my people’s experience are reaching you means that the sacrifices of my grandpa weren’t in vain — that his resilience paid off. The Black Egyptian is not some sort of mythical creature nor some sort of docile sage. Black Egyptians suffer once through omission from the narrative of Egypt, and twice by belonging to it. So, for you, across the globe, to be able to sit with what that means for millions of people is a victory: a redemption for my people after years of sacrifice.

I recall the story behind one of my favourite songs: “El Leila Ya Samra.” The story goes that in 1962, Egyptian-Lebanese poet Fouad Haddad was serving time in prison, alongside many communists, political opponents, artists, and thinkers. Among them was Zaki Murad, a Nubian-Egyptian communist activist. Murad was spending another birthday in incarceration. The state of the country after its 1952 coup d’état, as well as the injustice and torture that befell him and his comrades, weighed heavily on him.

So, to cheer him up, Haddad wrote a poem about Egypt overcoming its dire challenges. He personified Egypt as ‘Samra’ — an Arabic description for a dark-skinned beautiful woman. Nubian musician Ahmed Mounib composed a song for the poem, and Nubian singer Mohamed Hammam sang it. Between the three men, “El Leila Ya Samra” was born to boost the morale of Murad and, by extension, their own morales.

To me, this story encapsulates so much of what it means to be both Black and Egyptian. We are tied to this country, have sacrificed a lot for it, and have fought for its betterment and freedom both internally and externally, but we have also often borne the brunt of its failures. Granted, we are not the only ones who have sacrificed, but the erasure of Black people in Egypt is its own violence.

Although hard times lie ahead for Aswan, she will overcome if we — like Haddad, Murad, and their companions — get through it together. She will overcome only if we see Egypt as who she is. Not the Egypt of the wealthy enclaves like Marassi and Tagamoa, but the Egypt of what we are made to believe are its fringes: the Egypt of Aswan, of Siwa, of Sinai. The Egypt of all those who don’t create the narrative but whose lives are shaped by what it omits.