Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, emerged in a period of intense scientific speculation and discovery. Reflective of many scientists in this age, the titular character Victor Frankenstein rejects neutrality in his practice and instead pursues science that embraces danger and vulnerability. Borne from his reckless curiosity is a monster whose creation is symbolic of the abundance of debates, ideas, and anxieties in science at the time.

Shelley brings attention to the intersection of science and philosophy by accentuating the different perspectives of life and the body that were present before her novel’s conception. In doing so, Shelley unlocks the beast that is interpretation. How does the mind’s will transmit to the rest of the body? What is life?

Animalists versus metalists

Numerous scientific phenomena are contained within the pages of Shelley’s work, the most prolific likely being that of electricity in connection to biology.

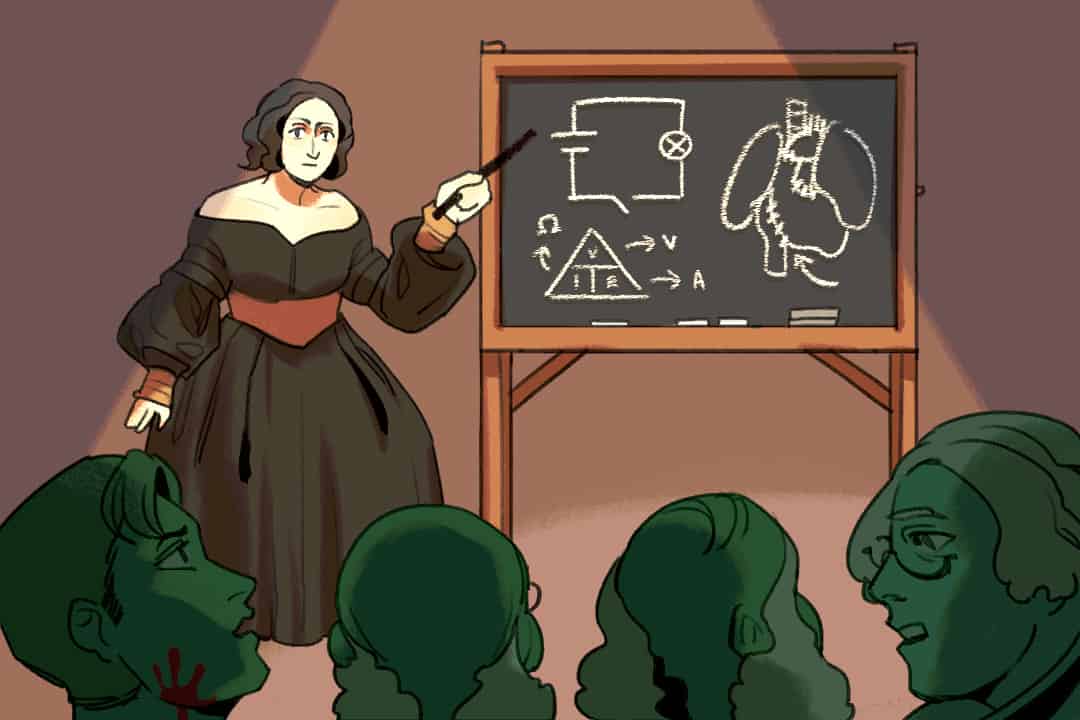

In the 1790s, this topic was widely debated by Luigi Galvani — a professor of anatomy at Bologna University in Italy — and Alessandro Volta — a professor of physics at the neighbouring University of Pavia. Together, they disputed over the idea of “bioelectricity” that seemed to link electricity and neuromuscular action.

In 1781, Galvani began a series of experiments connecting the nerves of frogs’ legs to a Leyden jar — a device that could store and release static charge at the user’s touch — and observed the contraction of the leg muscles in response to the current Galvani stimulated with the device.

He also found that the frogs’ legs often twitched when they were attached to the iron railings in his garden. These spontaneous movements suggested that electricity emanated from the muscle itself and that in circuit with the nerves, the muscles acted much like the Leyden jars, storing and releasing electrical current to cause movement.

But, in 1792, Volta’s experiments found that he could also induce contractions when he put two different metals in contact with the nerves of the frogs’ legs simultaneously. He undermined Galvani’s experiments with his proposition that the muscle responded to an external electrical potential and did not store it.

Volta’s experiments suggested the source of this electrical current to be contact potential: an electrostatic potential between two different conductive materials that have been brought into thermal equilibrium — the same closed system — with each other.

Together, the work of Galvani and Volta sparked a continuous debate about electric current generation between animalists — those who believed that electricity had a biological origin to induce muscle contraction, as displayed by Galvani — and metalists — those who believed in Volta’s ideas about contact potential.

Ultimately, both sides were right. The source of electricity in Galvani’s experiment was indeed the contact potential between two metals, supporting Volta’s theory. But, Galvani was also correct in his conclusion that electricity can be emitted from living tissues and that electricity transmitted through the nerve induces muscle contraction.

Galvanism, the application of electricity to the body, formed a link between electricity and life and sparked interest about reanimation. The landscape of Galvani’s laboratory — littered with dismembered corpses, mysterious instruments, and reconfigured muscles and nerves — was symbolic of his work on the intersection of life and death. It’s plausible that Shelley was influenced by his work, given that Frankenstein’s own scientific endeavours largely mirrored those of Galvani.

Vitalism versus mechanism

What is life and what is death? The ambiguity of this question cannot be answered by simply a reaction of muscles to a stimulus.

According to Joel Levy’s book, Gothic Science: The Era of Ingenuity & the Making of Frankenstein, Shelley’s circle of acquaintances debated multiple philosophical ideologies during the conception of her novel. The most dominant battle was between vitalism — the idea that life’s processes cannot be reduced to solely physical or chemical terms — and mechanism — opposite to vitalism, the belief that life can be explained entirely by physical and chemical phenomena.

Discoveries of the structural aspects of life — genetics, DNA, cellular signaling — have helped to elucidate the organization of the human body, but our consciousness remains to be fully and properly explained by science.

In Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein achieves reanimation by purely physical means, but the mental development of the monster speaks to both material and immaterial experiences. Learning, memory, and emotion stem from physical interactions in the monster’s nervous system. Thus, Shelley walks a blurred line of philosophical interpretation.

Infusing definition

The monster’s creation is a brief moment in the novel that lacks detail during a time in history thick with want for answers to life’s unknowns. By purposefully excluding all textual evidence of the methods used to create the monster, Shelley has allowed all these philosophies to exist simultaneously and the reader can freely interpret the mechanisms of life.

Victor Frankenstein says, “I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet.” Perhaps, we are our own sort of experiment: as we progress through life, imprinting experience on ourselves and those around us, we evolve.

No comments to display.