In the first week of June, U of T president Meric Gertler joined with other members of the Toronto community in signing a letter that called for an end to carding – a controversial practice that allows the Toronto police force to stop individuals and ask for identification based on the suspicion that they may have committed a crime. These individuals’ information is then recorded onto the Toronto Police database.

The practice has been widely criticized as an example of discriminatory policing as the subjects of carding are more often visible minorities than not.

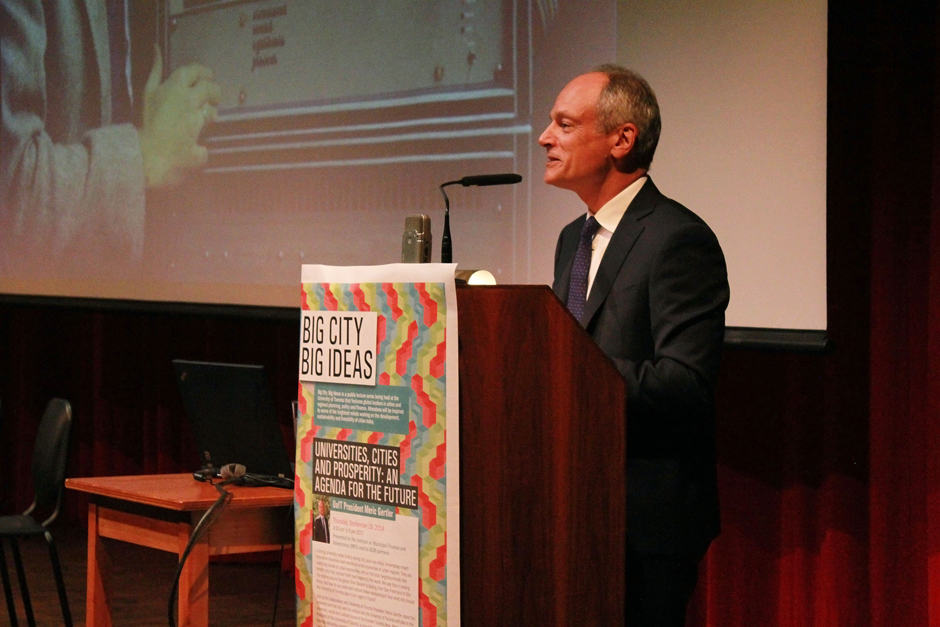

“It’s a moral issue. There is something deeply offensive about selecting people to stop on the streets… primarily on the basis of the colour of their skin,” explained Gertler when asked about his stance on carding.

Gertler’s role

Hashim Yussuf, a U of T student activist who has worked to protest against carding, shared his opinion of Gertler’s involvement with the issue: “It’s always good to have people in powerful positions, people who have a lot of say and a lot of power [weighing in]…But the leadership position should go to people who are most impacted by [carding], people from within the community.” However, Yussuf appreciates Gertler’s desire to branch out to marginalized communities.

Sania Khan, vice-president, equity, at the University of Toronto Students’ Union (UTSU), echoed Yussuf’s sentiments on Gertler’s participation. “The focus shouldn’t be on the fact that he gave it a quick signature and gave it the go ahead, it should be on the amount of people who have collectively come together, professionals, social activists, students — those who have been affected by the issue of carding — who have come together to pressure the administration, to pressure those who hold power to respond to their grievances. He’s doing his job and he should not be celebrated for it.”

Gertler notes that he has not received any negative feedback from the U of T community about his involvement. “As far as I can tell, people are quite supportive of the position I have taken,” he said.

Student awareness

Speaking to the general U of T populations’ awareness of the issue, Khan said that she believes that Mayor John Tory’s endorsement of an end to carding, and journalist Desmond Cole’s article for Toronto Life magazine on his experiences with the practice, have heightened discussion of the issue. Khan, however, is less confident about students’ awareness of their rights as citizens. “I feel like that’s something that is done on purpose,” she says. “We’re actually being repressed in ways that we just don’t realize, and one way is the lack of information that is provided.”

For Yussuf, working with others who have been carded is emotional and challenging. His efforts to eliminate carding include initiatives to inform minority groups most effected by this policy.

“Sometimes it is very traumatic,” says Yussuf, who has been carded several times himself. “It would happen a lot… like once a couple of months or once a month.” The first time he was carded, he was 16 and unaware of his rights.

Even after learning of his rights, Yussuf describes the difficulty in defending them. “It’s hard for me to say stuff. Because the police come up to you… they come up with two or three or four of them. And even if you say something, what’s stopping them from stopping you?”

Reform vs. elimination

Other than volunteer work, Yussuf has been involved with the Toronto Police Advisory Board and the Police and Community Engagement Review, trying to bridge the gap between the community and police in an effort to reform the carding policy.

“The police want to reform; they don’t want to get rid of it.” Yussuf believes that the police are pushed to reform due to public outcry, but the committee wants to completely eliminate the policy, which is a challenge. Yussuf considers the proposed reforms to be aimed merely at improving the police image, rather than addressing the issue at hand thus far.

In terms of working with those in power, Yussuf encounters difficulty persuading them to end carding. “The people who make the policy are very stubborn. Very stubborn. They won’t listen to you; sometimes the way they talk to you, they degrade you.” He has, however, met some police officers that support an end to carding but cannot openly endorse it out of fear of risking their job security.

When trying to motivate people to campaign with him, Yussuf finds that many are discouraged. “A lot of people feel that there is no point and that nothing’s going to change… people have no hope.”

Yussuf is marginally hopeful himself about the future elimination of carding. “With the support of the mayor and administration, I think it’s possible; it’s going to happen soon.”