I’ve been a music lover ever since I got a free Atomic Kitten CD from the movie theatre at the age of four. I’ve been attending music festivals since I was sixteen and concerts since I was ten. Living in the GTA and eventually moving to downtown Toronto has allowed me to experience the wonders of concerts on an incredible scale, but Toronto’s still not an official “music city.”

Do we really understand what it would take for Toronto to become a music city for attendees and policy makers alike? As a political science student, I understand that it is no easy task — music may be my escape from the policy world, but alas, human beings cannot escape from their own political realities.

With this in mind, I thought it best to pay a visit to the Toronto Music Advisory Council for answers. Toronto counicllors Michael Layton and Josh Colle explained the ins and outs of policy making when it comes to the arts.

The Toronto Music Advisory Council

With the rise of new festivals in Toronto like Field Trip and Bestival, it is becoming clear that urban policy-making needs to adapt to the changing climate associated with large festivals. It is with this necessity in mind that the Toronto Music Advisory Council was formed (TMAC). The council was created in 2014, and hosts a forum for prominent members of the Canadian music industry and city councillors to discuss much needed improvements and opportunities within Toronto’s music scene where topics of discussion include community complaints and economic development. The council does not currently hold a proactive, initiative based goal for policy; rather, it assesses the needs of the music industry within the city, with the hopes of strengthening its partnership with Austin, Texas, and eventually becoming an official “music city.”

Believe it or not, city councillors actually want a lot of the same things as concertgoers (though, I admit, my expectations are in some ways overbearing — like an O2 arena built by next year, and Broken Social Scene playing a concert every single day until the day I die). To my pleasant surprise, it seems as though there is hope that the city will work towards policies that will make festival organizing easier.

The city councillors

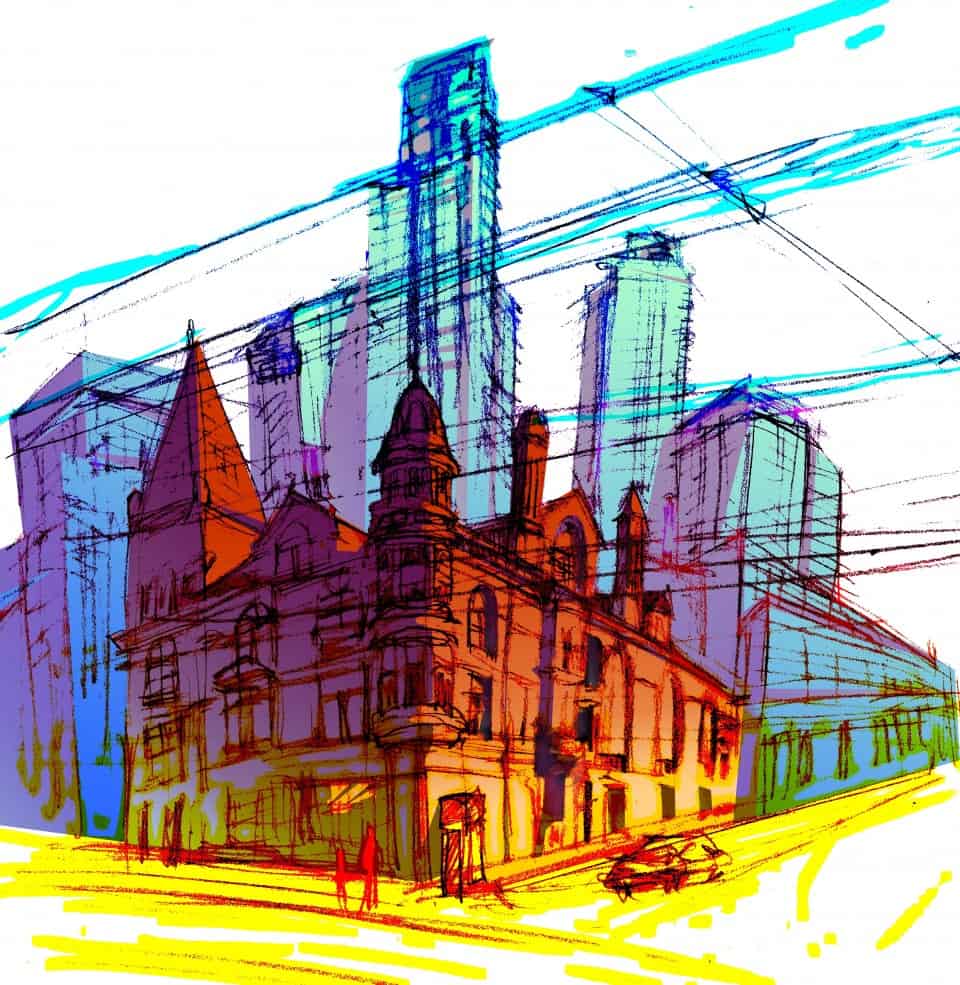

TMAC has only had one meeting. I guess it’s fair to say that everything is premature, but it seems apparent that the issues — ranging from the need for mid-sized venues to the time of last call — have already been brought forward. According to Colle, meeting the actual requirements of a “music city” may not be entirely feasible in Toronto. “One of the gaps in Toronto is landscape,” Colle told me. “We are missing probably two mid-sized venues, and one of the challenges we have is with the condo boom in the city, since it puts venues at risk.”

But according to Layton, there may still be hope yet. “We do have some opportunities with the redevelopment of Ontario Place, for example, and we haven’t quite realized all the potential of the CNE as a venue because of transit.” It’s clear that the development of venue infrastructure will be the largest obstacle in the city’s ability to grow, especially if smaller festivals and promoters hope to emerge. Thankfully, this hasn’t stopped the growth of home-grown festivals like Field Trip, located further outside the downtown core at the Fort York & Garrison Common.

“If you look at Toronto right now,” Colle said, “we do have home-grown [festivals] like NXNE and CMW, as well as Wavelength and many others. I think our role, as a city, is to turn those festivals into the next big thing. The [foreign festivals] that are coming are based on the market, but what we should do as a city is make the festivals that are a bit smaller right now become larger.”

But how do we go about increasing the size of these festivals? According to Colle, it’s the little things that count. “[The Toronto Urban Roots Festival] and Field Trip have become amazing festivals. Not only do they have local talents, but they are also on city sites. So how can we better assist them? Well, they need things like water and power sources, and those don’t sound sexy but they are practical realities that make concerts a success.”

Colle and Layton provided a clear explanation of the improvements Toronto would need to make in order to nurture a sustainable music scene. It’s not unrealistic for politicians to push for policies that will benefit us, but in sectors like the arts, how much control do we really want our councillors to have?

What we should expect from City Hall

The NXNE Action Bronson controversy presented the perfect scenario to assess the true power of city council, and in which situations they should interfere. I attended a panel at NXNE called “A Soundtrack of Violence,” where the discussion focused on whether we should support artists who glorify sexual violence, opinions on the NXNE decision to cancel Bronson in general, and strategies moving forward.

During question period, one of the solutions suggested was for an “empathy council” to be established at NXNE festivals. Said council would be comprised of a diverse group of people who would determine whether or not a policy was offensive or disruptive to their respective communities. Although initially the idea seemed promising, the more I thought about it, the more problematic it seemed. With an empathy council, City Hall would eventually be pressured into regulating content.

When speaking with Colle and Layton, it seemed as though the regulation on musical content would not be within the jurisdiction of the city. The response to matters such as whether or not Action Bronson should perform was not something the city could realistically regulate.

Go Demo-crazy

A common theme throughout the conversation with to Colle and Layton was community community response to concerts and festivals — whether by issuing a sound complaint or by protecting the Great Hall — then it had been at the very least discussed, if not somehow resolved, by the city.

“It’s been really neat to see how we’ve been able to work with the community and the operators to craft an event where people will love it, and people who live nearby can tolerate it,” Layton said, adding, “this is a win-win situation in my books.”

If we truly want to make Toronto a music city, it’s important that communities and promoters alike can work together to talk to city councillors about concerns regarding the protection of festivals and venues.

Looking to the future

Toronto has the potential to be regarded as a world-renowned music city. The political support exists, artists and organizers are itching to expand, but what’s missing is diversity.

The diversity of the crowds at shows has been changing — punk kids aren’t the only ones at punk shows, and Kendrick fans aren’t the only fans at rap shows. The number of sold out shows at venues has been increasing as well, and festivals like Unsound and Bestival have been picking Toronto as a key expansion point.

Well curated festivals with diversity draw crowds — take for example, Coachella, Primavera Sound, Governor’s Ball, or Lollapalooza. It’s clear that the music industry and listeners are making the decision that Toronto is becoming the place to be.