Last year, ExxonMobil received a subpoena — issued by New York’s Democratic Attorney General — in which its business practices were called into question. Reports indicated that the company had suppressed its internal climate change research in an effort to influence policy and maintain profitability, leaving shareholders and the public misled.

Among the fervent decriers of the subpoena was Oklahoma Attorney General, Scott Pruitt, who argued that the company was merely exercising its first amendment rights. Pruitt has repeatedly united with the fossil fuel industry in suing federal agencies for “overreach[ing]” regulatory procedures. He has attempted to quash the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Clean Power Plan, a policy aimed at reducing carbon dioxide emissions and encouraging the use of sustainable energy sources.

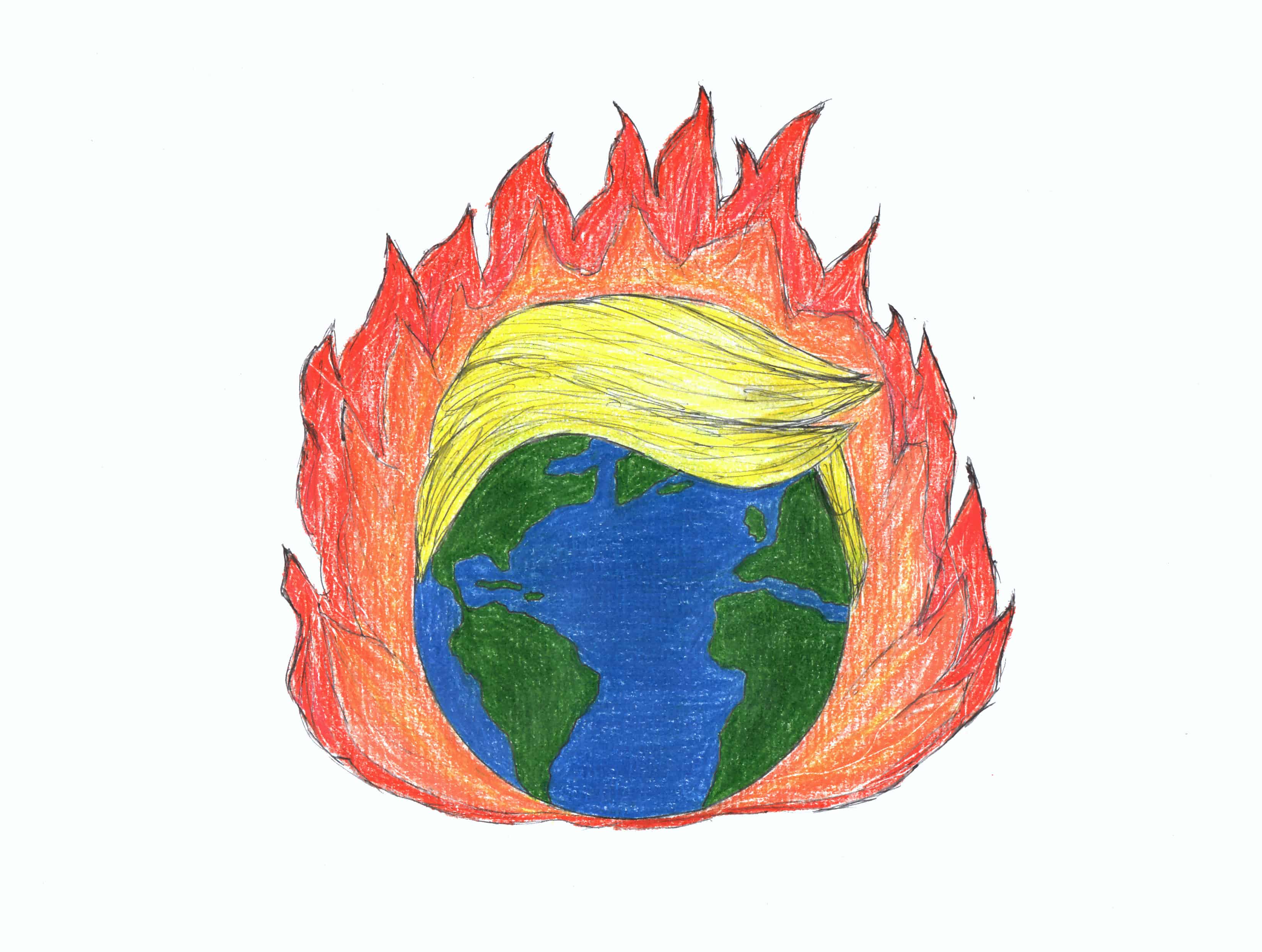

Recent revelations demonstrate that Devon Energy lawyers penned litigation documents for Pruitt’s case against the government. Coupled with his denial of climate change, Pruitt’s history raises concerns amidst his appointment to head the EPA by US President-elect Donald Trump.

Many have cited a gradual defunding and enforced futility of the EPA as looming possibilities. This would not be unprecedented: the last Bush administration cut federal EPA funding and worked to shut its libraries, effectively stripping the agency of its statutory independence. Much of the EPA content had not been digitized and was therefore lost.

The Internet Archive, a non-profit and open-access digital library, has spearheaded an End of Term project since 2008, a pre-emptive initiative to preserve online records in the face of shifting governments. The project has recently resumed in preparation for the incoming Trump administration.

Given the enormous amount of valuable data on the EPA website, some have taken matters into their own hands to prevent the potential loss of this wealth of knowledge. Last month, U of T hosted a collaboration with the End of Term project, a so-called “Guerilla Archiving Event” in which volunteers gathered to chip away at the massive undertaking.

Dr. Michelle Murphy, a Professor of History and Women and Gender Studies at U of T, who co-organized the event, was pleasantly surprised by the turnout. “I was very impressed that we were able to have 150 people show up on a snowy weekend day,” she said. “I thought the event was very successful, both in terms of getting the word out about the need to care about what’s going to be happening to environmental and climate data in governance in the United States, but also in terms of getting the ball rolling on data archiving and data archiving events that are in the pipes.”

Murphy argued that Canadians are well-suited for the task because many have had to ponder issues surrounding public access to data in recent years. For example, non-profit organization Evidence for Democracy was spawned in response to the Harper administration’s unfavourable attitudes toward science and its suppression of research communications.

Referring to these groups, Murphy said, “I think they both have something to offer in terms of an analysis but also in terms of helping our colleagues in the United States anticipate some of the things they might be seeing a few weeks from now.”

The event brought together people from various academic backgrounds and training such as coders, environmental scientists, social scientists, archivists, and librarians. A how-to toolkit was devised by contributors to assist similar endeavours at other institutions.

However, the project is unlikely to preserve the entire EPA library. Given the collaborative and open-access nature of the initiative, there are no enforced guidelines as to what should be saved; potential vulnerability of the data is likely to come into play in the selection process.

Murphy posited that the data most susceptible to loss include “the programs that have already been explicitly and gleefully justified for cutting like climate mitigation programs… Data that are harder to technically get and save than others [and] research and data… that you had to apply to get access to, that you have to do a freedom of information request to get.”

Although important, Murphy says preservation is not the only goal. “The next step is formalizing these best practices, working with archivists on [identifying] the conditions for credible copied data sets… What are the conditions [to ensure] security and public accessibility?”

Murphy recommends a chain of custody for data downloaded onto servers located or curated by a university. Data verification can rely on matching and mirroring scripts that detect tampering by comparing documents to a verified version. Metadata could be used to provide information regarding the original files, recent modifications, and so on.

Murphy adds that it is important to be “drawing together people to care about the future of environmental monitoring, environmental science, environmental governance, [and] climate change mitigation.”

Following Trump’s inauguration, she proposes creating a “100 days into the presidency” report to monitor environmental governance and mobilize organizations and the public accordingly.

The climate and its pollutants are not bound by national borders. Although it is not guaranteed that access to data will be hindered, Pruitt’s defense of ExxonMobil is but one example of his ambivalence – if not outright hostility – toward environmental information.

Murphy highlights the relevance of these issues to Canadians. Although the Liberal Party has signed pledges for open-access data and evidence-based governance, measures have yet to be implemented. She adds that “in Canada [we] don’t have strong laws on the right of access to information, research and data by our government.”

There is arguably no better time than the present to defend these rights on our home turf.