On September 8, 2017, Ontario became the first province in Canada to publicly release an official plan for the upcoming legalization of marijuana. The federal government seeks to legalize by July 1, 2018 but has left it up to individual provinces’ discretion to determine the finer details of how the substance will be sold, who will be allowed to consume it, and where usage will be permitted.

Whether Ontario’s plans will be successful remains to be seen, but the government’s emphasis on publicly-owned stores and privatized consumption could ultimately work to its detriment.

The framework issued by the Ontario government has three key features.

First, marijuana will legally only be sold online and in stand-alone stores run by a subsidiary corporation of the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO), thereby establishing a government monopoly of all legal consumption. This means all private dispensaries will remain illegal and will continue to be prosecuted.

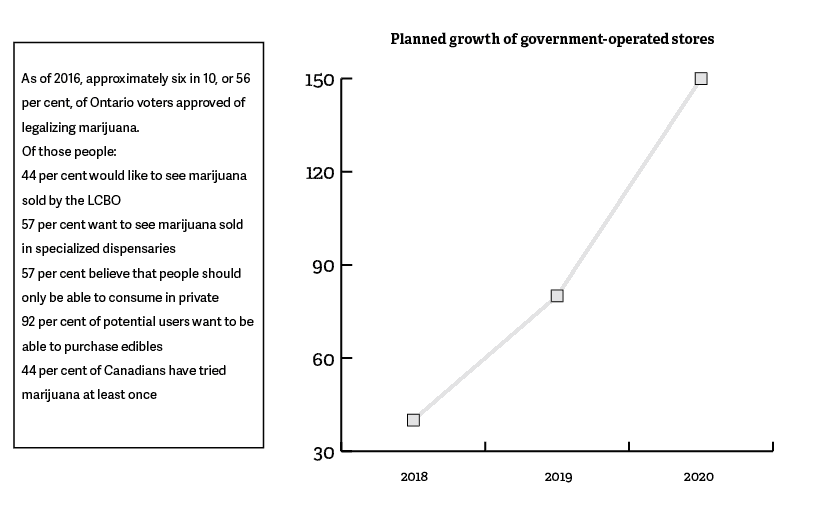

In this vein, the Ontario government plans to have 40 stores open across the province by July 2018, some in places where illegal dispensaries are already located. That number will increase to 80 stores by July 1, 2019 and 150 by 2020. In addition, an online system will be implemented by July 2018 to ensure the wide expansion of the market, especially in catering to more remote areas where it is less likely for official stores to be established.

The second feature of the framework is that sale and consumption are limited to those at or over the age of 19, in line with the legal alcohol consumption age. If caught, underage users will have their marijuana confiscated, though the government has stated the enforcement focus will be on “prevention, diversion, and harm reduction without unnecessarily bringing [youth] into contact with the justice system.”

Finally, all consumption will be restricted to private residences, at least for the time being. Private businesses catering to consumption, such as vapour lounges, will not be permitted.

For a number of reasons, the provincial government’s proposed framework for legalization is neither effective at discouraging illegal consumption nor inclusive of users. Allowing private dispensaries and designated consumption establishments to operate alongside government-owned stores would be a more effective approach to regulation.

Legalize private dispensaries

Jenna Valleriani is a U of T PhD candidate in Sociology and Addiction Studies whose research focuses on medical marijuana. Valleriani was disappointed but not particularly surprised when she learned Ontario had decided to pursue a government-controlled distribution model.

“I was really intrigued that the whole conversation was framed as an either or,” Valleriani said. Like many other critics of the proposed plan, she would like to see a mix of both government stores as well as licensed and regulated private stores in order to offer Ontarians “the best of both worlds.”

Contrary to popular perception, the dispensaries that currently operate in Toronto are doing so illegally — and this will not change under the new legalization plan. However, Valleriani believes that most dispensary owners would likely welcome the chance to become licensed and conduct their business legally. Dispensaries have been thriving for a long time in spite of police crackdowns and security issues — it is questionable whether the new regulations will do much to change that fact.

Restricting legal purchase to government-run stores also raises the question of supply. Establishing 150 dispensaries in Ontario — a goal that will only theoretically be reached in three years — is nothing compared to the high number of illegal dispensaries that are currently supplying users with their product. Legitimizing just a fraction of establishments will severely limit access, even with online sales.

Though Health Canada has doubled its staff to accelerate the licensing process for marijuana producers, many industry experts estimate that customers will still face shortages in the first few years of legalization due to lack of supply. Shortages, in turn, would send customers right back to the illicit market, which is exactly what the government is trying to avoid.

Private stores are also popular for the sheer variety of products they offer. Valleriani believes it is highly unlikely that government stores will sell oils and edibles — products that consumers have been obtaining from dispensaries over the years.

On top of this, the continuation of policing, shutting down, and prosecuting dispensaries is a wasteful burden on already strained law enforcement and court resources. Targeting dispensaries in this way has been largely ineffective; where one store shuts down, another pops up in its place. In fact, alleviating this burden from the criminal justice system was one of the main reasons for decriminalizing marijuana in the first place. If Ontario continues to shut out private establishments from the market, it will be back to square one.

Working with dispensaries instead of against them could avoid all of these problems; a more open, mixed system of regulation has better chances of squashing the illicit market.

Legalize public consumption establishments

The plan also restricts consumption to private residences for the time being. The government has expressed plans to consult on the “feasibility and implications of introducing designated establishments where recreational cannabis could be consumed” — a proposal that is vague and shows a lack of real commitment to legalizing said establishments, which ought to be a priority moving forward.

The current plan’s emphasis on private residences as the only place for consumption is not inclusive, and it prioritizes homeowners. It leaves people who rent, lease, live in shelters, or are homeless without a safe or legal place to consume. Residents who don’t own the buildings they live in are left at the whims of their landlords as to whether or not they are allowed to consume in their homes. It is well within the powers of condominium boards or apartment building managements to ban marijuana on their property. Therefore, these residents are put at increased risk of incurring criminal charges when they inevitably turn to public places to consume.

This rule also disproportionately affects students of legal age, including those who live on residence during the school year. Dormitories are owned and controlled by the university, and U of T is a public establishment. It is unclear whether students will be banned from consuming marijuana on campus — particularly in light of recent announcements that the university is investigating a smoking ban. Legalizing designated establishments for consumption would provide students with a safe alternative.

At the same time, Valleriani recalls a professor at Trinity College, now retired, who was prescribed marijuana for medical purposes. Accommodations were made to set up a sort of ‘vapour lounge’ area for him in the basement of the college. The existence of bars near and on U of T campuses, events where drinking is permitted, and the designated smoking spaces currently in place on campus show that it is possible to make allowances for the consumption of controlled substances.

The idea of creating a designated place for consumption at U of T is not as outrageous as it may sound, and Valleriani thinks universities will ultimately need to “figure something out.” Such an arrangement, however, would require the legalization of designated establishments for consumption, an option that the proposed regulation framework does not allow.

With nine short months until marijuana legalization launches in July, little time remains for Ontario to perfect its plan. Costs of purchase, whether the product will be taxed, and where government stores will be set up are decisions that have yet to be made. In this time, the government also needs to critically evaluate their plan and recognize its weaknesses in achieving the ultimate goal of eliminating the marijuana black market. Legalizing private dispensaries and designated consumption establishments will help bridge those gaps.

Ramsha Naveed is a third-year student at Trinity College studying Political Science.

Editor’s Note (September 25): This article has been updated to clarify that the sentence “a more open, mixed system of regulation has better chances of squashing the illicit market” is the opinion of the author and not Valleriani.