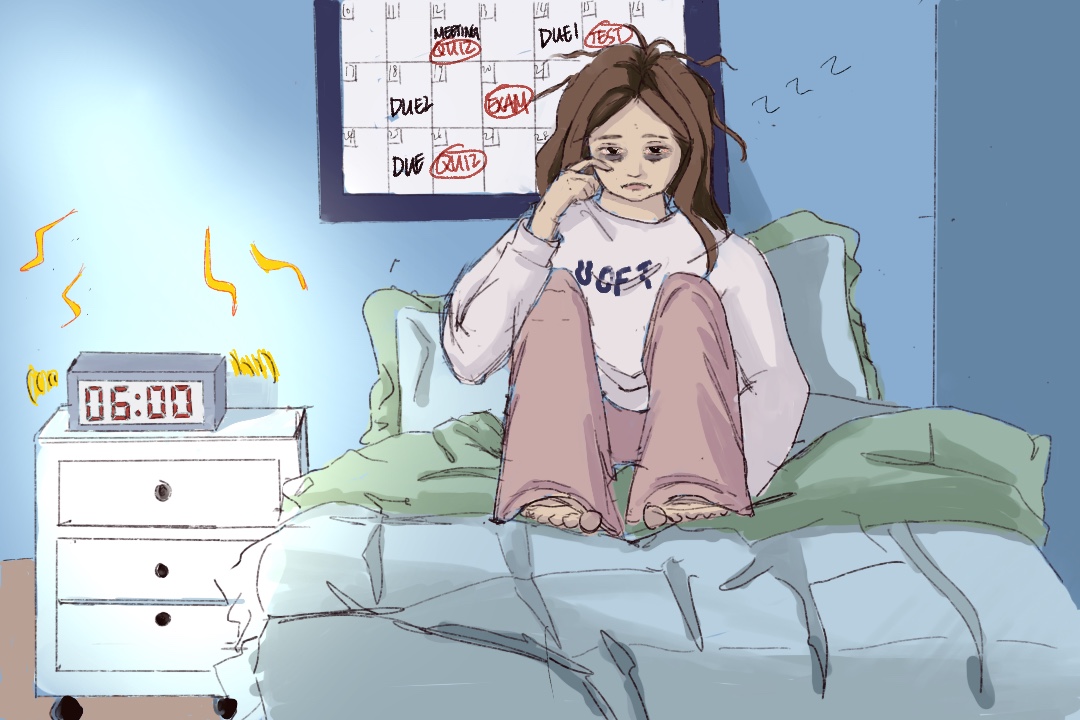

Sleep deprivation is one of the hallmarks of any stressful midterm season. To stay awake, university students may start consuming cups and cups of coffee, but the long-term effects of overconsuming caffeine can negatively impact both physical and mental health. Sleep can also take away precious hours that might otherwise be used to cram for that big test.

Why do humans waste so much time sleeping in order to function? The Varsity set out to investigate.

The origin of sleep

In the Journal of Circadian Rhythms, Penn State University researcher Andrew Freiberg proposed an explanation for how sleeping enhances the fitness of organisms. All species face challenges when adapting to the changing seasons or the cycle of day and night. Freiberg thinks that sleep might be an evolutionary way of adapting to the differences between an organism’s environment in both daytime and nighttime — being awake and alert during the day and asleep during the night is one way of taking advantage of each environment.

Sleeping at night allows organisms to prepare for the exertion of foraging in their time awake. However, there is an interesting evolutionary tug of war between sleep and insomnia. According to a 2020 paper on insomnia, when faced with immediate dangers or threats, organisms are able to override their need to sleep. This means that occasional insomnia may be another normal part of human survival.

If you fast forward to the present day, many of the acute stressors that humans experience are predominantly anticipated and less deadly compared to imminent physical threats of being chased down by predators. As a result of dramatic changes in lifestyle from our ancient ancestors, traits such as acute insomnia are no longer advantageous to us and may even be harmful to us.

This constitutes what researchers, including UTM anthropology professor David Samson, called a “gene-environment mismatch” because the adaptive trait of acute insomnia no longer suits the environment we find ourselves in.

One example of the harms of insomnia that’s relevant to university students is pulling an all-nighter before going into an exam. While those few extra hours of study might seem crucial, the sleep deprivation caused by an all-nighter may in fact lead to heightened and counterproductive stress levels.

With more than 20 per cent of the general population in Western countries experiencing symptoms of insomnia to varying degrees, the adaptive physiological response to stress could easily become disruptive to a healthy sleeping routine.

How much sleep do I need?

In 2015, the National Sleep Foundation (NFS) published the first ever peer-reviewed paper on recommended sleep time across different stages of life. The NFS appointed an international panel of 18 experts, including Professor John Peever from U of T’s Department of Physiology, to conduct an evaluation of scientific literature about sleep. In the end, the panel reviewed more than 300 scholarly articles focused on medical and scientific research.

The panelists split people into nine categories for their evaluation, ranging from newborns to older adults. The results indicated that the recommended amount of sleep for adults aged 18–64 is seven to nine hours per day.

Despite the recommendation, the panel did emphasize in their article that it is possible to have a healthy amount of sleep outside the proposed range without any negative impact to cognitive function. There are many other factors that can impact the restorative properties of sleep, such as the quality or timing of sleep. It’s only when an individual’s sleep time significantly varies from the normal range that medical attention might be necessary.

Tips for better sleep

The ongoing pandemic has instilled a strong sense of uncertainty in people’s day-to-day lives. Samson shared some of his practical tips for a good night of rest in a U of T News article.

According to Samson, eating sends a signal to the body that conflicts with its circadian rhythm — the body’s internal biological clock. Simply scheduling your dinner around three hours before bedtime, reducing your intake of stimulants, and snacking less frequently can help your body wind down at the end of the day.

Another helpful tip is to turn off screens and electronic devices at least an hour prior to your desired bedtime. Constant exposure to news updates and blue light emitted from screens can be stimulating distractions that prevent one from falling asleep. So lights out and sweet dreams!