I first ventured into Neil Gaiman’s acclaimed The Sandman comic book series during the winter of 2018. Before then, my main image of its title character wasn’t the overseer of children’s sleep from folklore but the iconic Spider-Man villain of the same name — in hindsight, this confusion was revealing of my literary innocence.

My cousin had recommended The Sandman to me during one of our summer family reunions. I’d always thought that this cousin had stellar taste in books, so I finally decided to vet their recommendation.

As I explored the series for the first time, I simultaneously became exposed to the existential dread of pursuing an undergraduate English degree. I’d spent my formative years as a reader devouring comics and superhero stories; I’d immersed myself in literature I thought was ‘low culture.’ This was a sharp contrast to all that awaited me in the classroom; I now found myself studying works that the world collectively considered to be ‘high culture.’

My biggest dread, however, were the classics. I was on nodding terms, at best, with the canonical, celebrated works of literature that awaited me in my studies — the painful reminder that my ignorance would follow me into the semester.

Upon arriving at U of T that September, the first connection that I made was with another aspiring English student, Dan. In our first conversation, he casually mentioned that he was in the middle of reading Don Quixote, a seventeenth-century Spanish novel, for his Vic One class. I nodded and pretended that I knew what he was talking about whenever he referenced windmills. The next time we spoke, when he casually discussed Jacques Derrida’s theory of deconstruction, my sense of inferiority was only heightened.

Years later, as we got to know each other better, I came to appreciate Dan’s friendship. But back then, the best I could do was tolerate his company. Effortlessly well versed and curious, Dan represented the ideal member of U of T’s English program community — this archetype was everything that I wasn’t. When we both found ourselves in the year-long English course ENG140 — Literature for Our Time, I carefully avoided him throughout the year.

It’s not that I solely blamed students like Dan for my imposter syndrome — there was also the factor of impressing my uber-cool instructor, nationally renowned Canadian literature scholar, Nick Mount. Mount began our first lecture by telling us, “If you’re here, I assume it’s only for one reason: you want to know the truth.”

This kind of truth, I’d later learn, was only found in fictional works. It was the kind, Mount would later make me realize, that often lies where we aren’t looking for it. For some, this truth lies in the oldest works of literature; for others, like myself, it can only be contained in a boundary-pushing comic book series from the ’90s.

My introduction to “universal stories”

With his iconic fedora and dramatic classroom persona, Mount could pass as Indiana Jones with academic tenure. He was the kind of professor who played music in class before the start of every lecture, with all the songs being thematically related to the book we were reading in class that week, and he fielded song recommendations from students. He was the kind of professor who made each person in his auditorium feel validated, whether they were a nebbish bookworm or were just looking for a credit.

As great as Mount was, his larger-than-life teaching presence alone wasn’t enough to get me invested in the assigned readings. I spent the following fall semester pretending to read the texts on our syllabus — the anointed “literature of our time” — and preparing something thoughtful to say about them. Mount began the course by walking us through the foundational works of modernism: a movement that emerged at the turn of the twentieth century defined by formally ambitious works of fiction espousing universal truths and often reimagining older stories.

The first text that we examined was T.S. Eliot’s infamously cryptic five-part poem, “The Waste Land.” Running at 433 lines, the text felt epic in the literal sense of its length but also epic in the literary sense. In the poem, Eliot draws on a slew of allusions to older stories from myth and literary canon — with helpful explanatory footnotes from the publisher to aid unfamiliar readers — to portray the fragmented pieces of timeless stories that are entrenched in modern life.

Like many first-time readers, I had difficulty understanding or appreciating Eliot’s poem on first brush. But reading the first The Sandman story arc, “Preludes and Nocturnes,” not long after, inspired a similar ambivalence. I was expecting Gaiman’s comic to follow the typical generic beats of a comic-book superhero story — and in some respects, it does. The story centres on the series’ protagonist, Dream, going on a journey to retrieve his powerful magic items and stopping a supervillain hellbent on destroying the world.

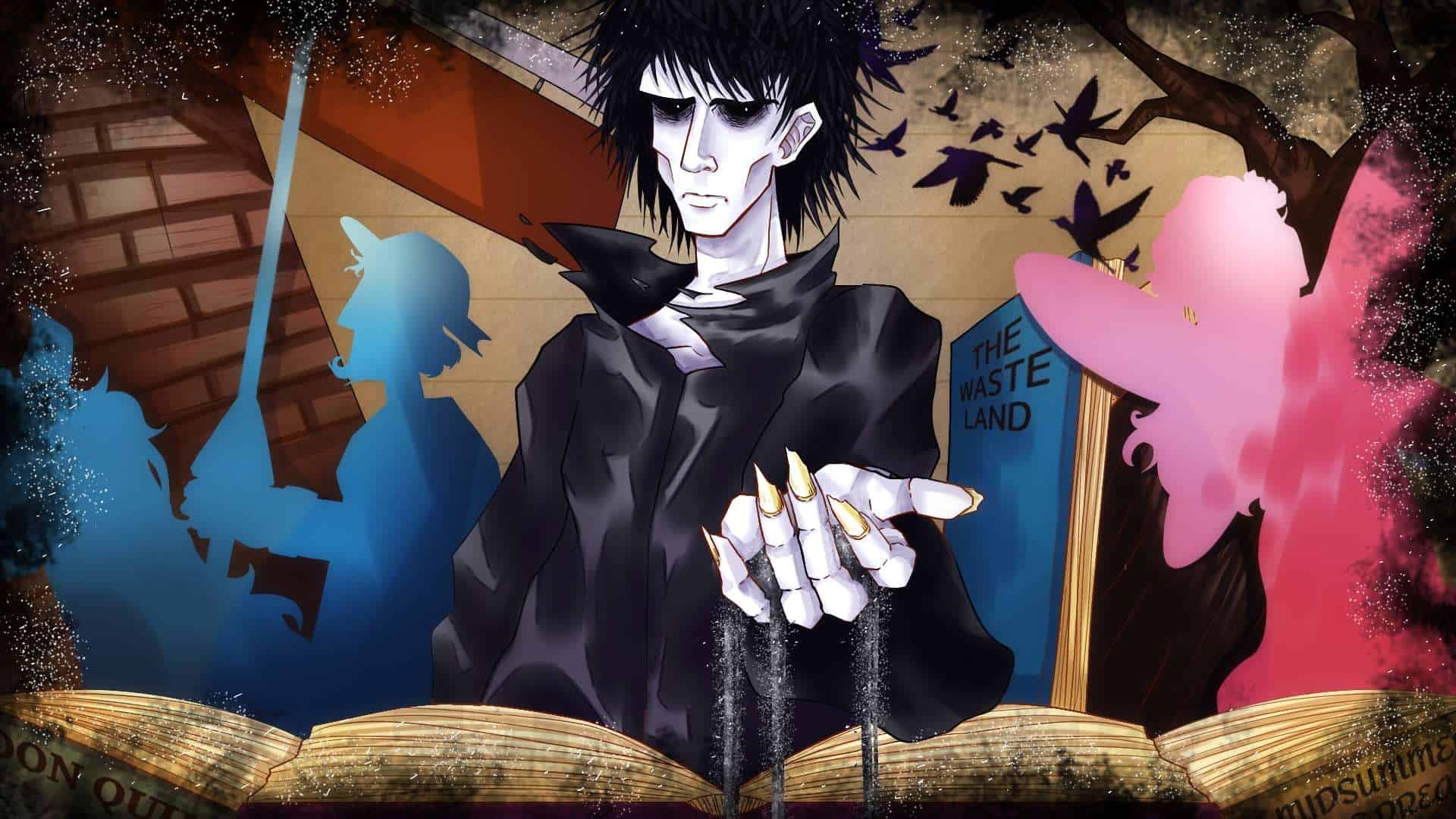

Only through further engaging with The Sandman did I realize Gaiman’s broader aims. Taking a leaf from the pages of the modernist handbook, his series draws from timeless stories to enhance the meaning of the stories we tell today. Just as Eliot reinvents the Arthurian “Fisher-King” and the quest for the Holy Grail in “The Waste Land,” so too does Gaiman reinvent the folktale character, the Sandman — who was an eighteenth century German folktale character before becoming a Golden Age DC Comics superhero — into a personified version for storytelling.

Even the protagonist’s alternative name, Morpheus, hearkens back to ancient storytelling; Sandman’s namesake is the Greek god of sleep. The larger ensuing story of The Sandman follows Morpheus’ attempts to rebuild his fragmented realm in a mission to restore order and meaning to humanity’s collective imagination. He seeks to make sense of the world through the power of universal narrative, just as Eliot attempted to do in his fragmented postwar world through “The Waste Land.”

But I didn’t understand this back then. My literary palate was still developing, and the prospect of continuing eight more volumes of a comic series, when I already had a whole list of other assigned texts that I had to pretend to read, was just too much to surmount. I put The Sandman and other comics on hold — but they found a way to catch up with me.

“Many of you may be more familiar with comics than me,” Mount admitted to us at the start of the final lecture of the year. To capstone our syllabus, at the end of the winter 2019 semester, Mount included Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan, a novel-length comic about a superhero-obsessed kid obsessed who refuses to grow up. A frisson of pride and anticipation coursed through my veins as I heard the opening words. For once, I felt in the know, ahead of the game, or at least that my knowledge was on par with my peers.

Soon after, Mount asked us what comics we read, if any. Some plucky and keen students shared their answers. I was hesitant to speak out of turn, being a perennial classroom wallflower. As a compromise between my shyness and my desire to impress my instructor through my unusually above-average literary knowledge, I approached him after class to share a comic recommendation. It wasn’t The Sandman though, and in retrospect, that was probably the biggest missed opportunity of my undergraduate career.

Old stories, new forms

The opening line of “The Waste Land” — “April is the cruellest month” — came to feel eerily resonant months later with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Halfway through my English degree, I was forced, like all my other peers, to continue my studies remotely. I found myself back home, once again living on Sandman’s crescent.

Once my classes ended, and in absence of anything else to do during quarantine, I had plenty of time for pleasure reading. In July, Amazon’s company, Audible, released a dramatized audio adaptation of the first three volumes of Gaiman’s comic series. It was simply titled The Sandman, which proved the perfect reentry point for me into the books I had abandoned.

Every day that summer, I ventured to the playground swings, situated like an island surrounded by a sea of sand. In a desperate way to escape from my mundane domestic surroundings, and to try and recapture some innocence and capacity for wonder, I sat and swung away, with Audible’s The Sandman playing in my headphones. On that day, I listened to the book’s final episode, “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

As it turns out, even authors of the classics themselves aren’t afraid to buck against the common perceptions of literary high culture. Eliot was a notable detractor of Hamlet, and even wrote an essay titled “Hamlet and his problems.” In the essay, Eliot called the play an “artistic failure”, writing that, “most people probably thought [it] a work of art because they found it interesting, than have found it interesting because it is a work of art.” Eliot argued that Shakespeare created his title character to possess excess emotion, which has no equivalence to the action of the character and the other details of the play.

By contrast, The Sandman features Shakespeare in three comics: “Men of Good Fortune,” “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” and “The Tempest.” In these works, Gaiman extends the logic of Shakespeare’s play, disseminating its meaning, and projecting it into new contexts. These pieces stem from Gaiman’s acknowledgment of Shakespeare’s pieces as works of art; if his series has an overarching message, it’s the recognition of an old story’s enduring and timeless power.

Nowhere is this better exemplified in The Sandman than in Gaiman’s treatment of William Shakespeare, and the series’ landmark 19th issue, “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” In the story, Shakespeare agreed to write Midsummer for Morpheus as part of their bargain. Shakespeare and his acting company travelled through the countryside to perform the play when Morpheus opens a portal between dimensions and invites the fairy realm’s denizens to watch the play. The company premiers Midsummer for Titania, Oberon, Puck, and many other characters on whom the play is based in attendance. In writing this, Gaiman provides an origin story for Shakespeare’s immortalization in our modern culture, as the English language’s greatest writer, someone who cemented his legacy through writing universal stories.

The 19th issue of The Sandman sees William Shakespeare staging the premier performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream before an audience of Morpheus and the mythical faerie beings portrayed in the play. The story won the World Fantasy Book Award in 1991, the first — and only — comic to win the prize.

As he did with the original The Sandman comics, Gaiman brought an old story to life in a new form, and this time it was in oral form. While the audio drama features a star-studded cast of voice actors bringing each character to life, Gaiman himself, among others, is one of its narrators. The author renders the narrative events from the comic, depicted visually in their original form, into words, and reads them aloud into existence — to quote Shakespeare, Gaiman “turns them to shape and gives to airy nothing a local habitation and a name.”

Gaiman, like his fictional protagonist Morpheus, and even Shakespeare, demonstrates the transformative power of storytelling. The episode ends with him sharing two ominous events yet to unfold, through terse narration: “Hamnet Shakespeare died in 1596, aged 11. Robin Goodfellow’s present whereabouts are unknown.” Then the credits roll.

The Sandman reinforces the idea that the death of Shakespeare’s son, Hamnet, inspired him to compose literature’s greatest tragedy that we know all too well today, Hamlet. Gaiman assembles disparate fragments of narrative — from mythology, history, and great literature — to add meaning to our understanding of life. In The Sandman, Gaiman accomplishes what any great author seeks to do; just like his character Morpheus, he uses the power of imagination to shape reality.

I had never read nor watched a performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream before listening to The Sandman on Audible — but, like the play’s characters, I too felt like I had awoken from a trance I wasn’t even aware of. I walked home after that, my feet grazing the playground sand. Rain had soaked into my clothes, but I couldn’t care. From that moment onward, I started to make my way through all The Sandman comics I had missed, and eventually, Shakespeare’s play too.

The truth in plain sight

“We already have an Eliot, and we don’t need another one,” wrote Mount in an email to me at the beginning of my undergraduate career. He was attempting to assuage my first-year existential crisis, one spurred by the thought that if I couldn’t marvel at the canonized literature of our time, I was somehow unfit to be an impactful writer myself.

The single grand truth in “The Waste Land” is contained in two onomatopoeic letters at the poem’s end: “DA.” On their own, these characters are nothing extraordinary — but, like any work of literature, they’re open to interpretation. If readers are willing to go look for this interpretation, then they’ll find what the truth of that work is to them. In hindsight, the truth that I was looking for — the truth that led me to The Sandman — was right there all along, during one of the earlier ENG140 lectures.

“I don’t know what it would take to get 100 per cent on an English essay,” Mount conceded to us in class that afternoon. He drew a breath; a few of my classmates awaited a response with bated breath, but the answer didn’t matter to me. All I knew was that I would leave our classroom in Isabel Bader Theatre content with a final mark somewhere in the 80s range, the usual residue of inspiration from Mount’s words, and an unread comic book on loan from the library, waiting for me when I returned home.

Professor Mount exhaled: “I’d guess you’d have to be Shakespeare.”

Editor’s note (November 19): A previous version of this article called the final episode in the Audible version of The Sandman “Dream Country.” In fact, the episode is called “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”