Content warning: This article discusses death and mentions substance use disorder.

On September 13, The Centre for Research & Innovation for Black Survivors of Homicide Victims (The CRIB) — a multidisciplinary research initiative based out of the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work — held a screening of their film titled Invisible Wounds: Stories of Survivorship.

The CRIB created the Invisible Wounds project to provide an opportunity for African, Caribbean, and Black (ACB) Canadians who have lost loved ones to homicide to share the impact that these deaths have had on their mental and physical well-being. The organization led focus groups with ACB survivors of homicide victims and worked with them to digitally share their stories. The project also aimed to better understand the unmet needs of survivors in Toronto.

The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council — a federal agency that provides research grants — funded the Invisible Wounds project. The CRIB led the project in collaboration with StoryCentre — a group that works with organizations and communities to share stories through various platforms — and other community organizations.

The CRIB previously held a screening of the film at Innis Town Hall on September 13, 2022.

Stories of the survivors

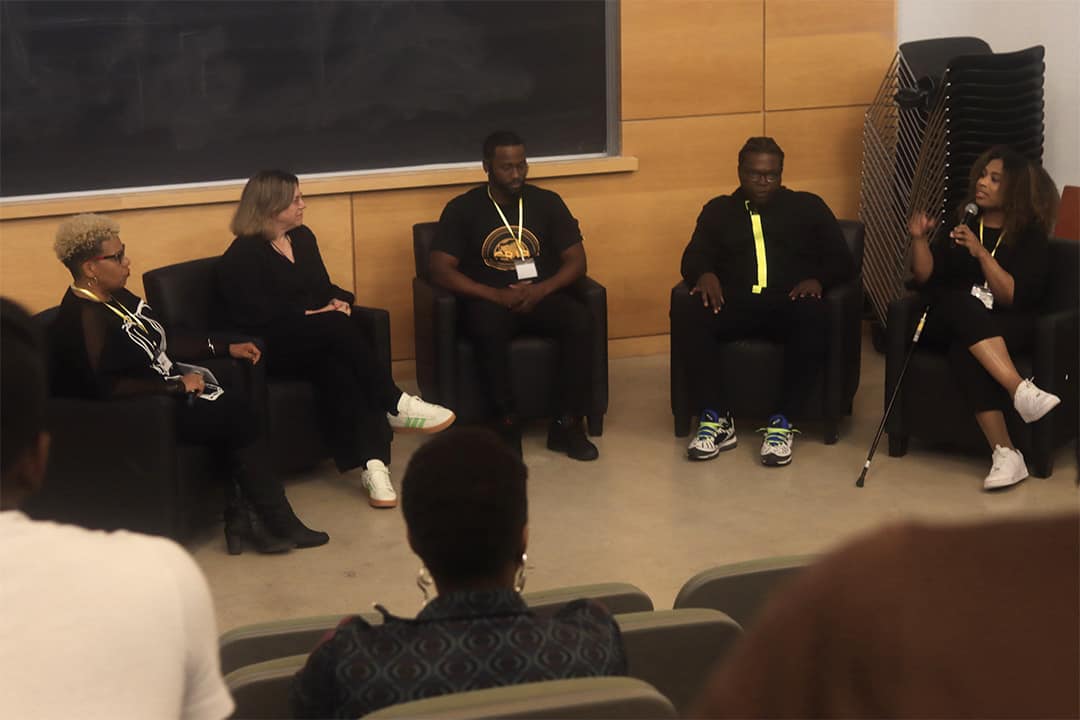

After the film screening, Tanya L. Sharpe, founding director of The CRIB and an endowed chair at the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, led a panel discussion where participants shared their experiences working on the movie project and why they chose to take part.

“In so many ways, this project and coordinating this project was healing for me as well,” explained Jheanelle Anderson, a social worker and senior research assistant at The CRIB whose research focuses on disability justice and Blackness. “There were not a lot of Black faculty at the school of social work, so I was keenly interested and I looked up [Tanya’s] research.” Anderson facilitated interviews and listened to stories of survivors as part of the project. She told the audience that other folks’ stories felt similar to her own.

The panel also included survivor storytellers such as Tito-tae Sharpe, who currently works as a community youth supervisor with the City of Toronto Parks and Recreation; Deshawn Hibbert, an aspiring social worker who served as a neighbourhood ambassador for the project; and Rani Sanderson, the Canadian projects director at StoryCentre Canada, who facilitated the digital storytelling aspect of the program and edited the film.

Tito-tae Sharpe told the audience that he decided to participate in the project to actualize the values of the person close to him who passed away. “The person who passed away… he would come to people’s houses and paint for free. He would take all of the people’s garbage, come to my house, ask for a fruit, just little things like that. You remember a lot of little things that happened around that time period. And so, you are just trying to pass it on,” he said.

According to Tito-tae Sharpe and Hibbert, the 13-week-long project started during COVID, with participants meeting on Zoom.

“At times, it was all black screens — so we’re opening up, being super vulnerable to a black screen that we don’t know,” said Hibbert.

He described wondering about other participants’ views of him. “What is this guy’s facial expression behind the screen? What does he think? Am I soft?” Hibbert said. “That part was challenging.”

Tanya Sharpe added that they found it difficult to have participants turn on their cameras and to help them feel comfortable. Panellists shared that sitting through interviews and reliving that pain also felt difficult. Sometimes, they had to stop during interviews because things became too hard.

“I used to grieve with substance abuse, or just being depressed or down,” said Hibbert in an interview with The Varsity. As part of the program, he learned to channel his grieving energy differently and found joy in sharing that with his community.

Hibbert felt happy that people came out to the film screenings so that the program’s message could continue to spread. “I’m looking forward to pushing that narrative that… in the right setting, hurt people can help people for a better day, for a better tomorrow, for a better future,” he said.

The CRIB

Tanya Sharpe launched The CRIB in 2019 with funding from the university’s division of the Vice-President and Provost as well as the division of University Advancement. According to its website, The CRIB focuses on advancing research and policy for Black survivors of homicide victims through community-engaged methods. The centre focuses on understanding how the traumatic impact of murders can affect surviving family members in Black communities.

In 2022, The CRIB released a report and interactive map based on homicide data from 2004 to 2020. The data demonstrates that majority-Black neighbourhoods in the GTA are not only disproportionately affected by homicides but also include fewer grief supports for survivors.

The report estimates that on average, each death by homicide strongly impacts at least seven to 10 family members and close friends, with an estimated 3,850 Toronto residents affected by the deaths of loved ones by homicide. It also discusses how social determinants that drive homicide rates — including lack of employment opportunities and education, mass incarceration, and continual retraumatization that breaks down social support networks — are often fueled by anti-Black racism.

At the screening, Tanya Sharpe told the audience that, in the next few months, The CRIB plans to launch a similar program with younger participants between the ages of 12 and 16 in the GTA.

No comments to display.