You learn things while cutting up other people’s babies.

For one thing, Coach House books are very well made. Laying the scalpel to the inside backbone of their stiff, pebbly-textured pages, right against where the paper meets glue to form the spine, I panicked.

Anyone who belongs to this strange army known as “readers” understands the powerful totemic aura that extends from the words to their vessel, from the story to the book.

We may scuff their jackets as we stuff them rudely into bags and hurry off the streetcar. We may leave them face-down, butterflied on the couch while we wander off to make dinner. We may use all sorts of strange and inappropriate objects as bookmarks. We may even leave them in the bathroom, after which their pages look like they’ve had a bad perm (and let’s admit it, they were dog-eared anyway). But by god, we would never—never—intentionally do harm to a book. The above-mentioned abuses are merely the rough-and-tumble signs of our love. This is the wall that proponents of e-book readers find themselves still butting their heads against in the age of the iPod: nowhere on a Kindle is there an app for tearing off the corner of your favourite pages, putting them in your mouth, and swallowing. Such was the love that the Young Adult author Kit Pearson had for her favourite stories as a child: she needed to ingest them. Irrational, maybe, but ritual has never claimed its immense power from the rational world. Anyone who has ever performed the Eucharist should understand this.

This was the river of thought moving miasmic through my mind as I placed the snappy Coach House terriers on the operating table and viewed them there with increasing dread. I am a reader. Since being infected somewhere near the age of six, I have daily fought to control a sometimes overwhelming appetite for text. “What the hell am I doing?” I thought, as I held the knife to Maggie Helwig’s Girls Fall Down, which was shortlisted for the 2009 Toronto Book Award. I looked into its eyes, knowing that someone just a block away had put love and care into this thing and trusted me to treat it as a friend. And now I was about to cut it to shreds.

“This is going to hurt me more than it’s going to hurt you,” I promised, which may have in fact been true.

How did I get to this point? A psychological profile of this mass murderer might note that balancing opposite my love of books is a life-long status as a collector, beginning with bottle caps, stamps, coins, then extending to records, books, and images, and then on to more esoteric collections, such as my collection of strange experiences. The thing about collectors is, they aren’t healthy people. They are obsessives who stress the wrong syllable; they love, but that love might be misplaced. Knowing this as a reformed collector, I can recognize that, while no doubt there are things that are precious to us, I distrust preciousness. I prefer, instead, the wisdom of contemporary forest preservation. If you want the forest to live, sometimes you have to let it burn.

The first cut was the hardest. But after that, the rest of the slaughter was easy.

This adventure began innocently enough last October. The leaves were still on the trees, there was light for a good part of the day, and I was in my office, editing stories for the last issue of The Varsity Magazine, when I was struck by a paragraph in Chris Berube’s article on copyright reform, “The Death of the Artist?”

“This type of artistic thievery has a rich history,” I read, as U of T instructor Martin Zeilinger explained to Chris how “copying someone’s work was the highest level of homage or respect that you could pay to a venerable author.”

Dada collage in the early 20th century, for example, was one of the first instances where artists would actually physically rearrange their influences into a new work of art. Last year, the copyright documentary RiP: a Remix Manifesto pointed out that this ethos has been especially present in music, which has its own language of borrowing.

This wasn’t entirely news to me, though something about the historical aesthetic assumption—copying as a form of homage—placed in relief against our contemporary discussion of the mashup—which often deals more with legalities than it does with aesthetics—clicked.

I assume you are already familiar with the overwrought discussion plaguing the media and entertainment industries at the moment on whether technology is destroying culture and the trustworthy production of information. Here, “technology” is often defined as that which is new, as opposed to the old, inherited tools that were revolutionary at the time of their inception, yet on which whole industries now base their livelihoods. Cue Gutenberg. One very loud and obnoxious side of this discussion yells over the voice of others that it’s fine that change has defined our cultural development for the past several millennia, but as of 2010, that evolution should come to a stand-still for the benefit of a very few.

While reading Chris’s article, I was struck by how differently the cultural industries have moved through this discussion, each at their own different pace, with book publishing probably the slowest. And while digital books and e-book readers are becoming more popular, consumers do not have the technology, as they do with sounds and images, to effortlessly and speedily digitize a book for themselves. Thus, while e-book readers (essentially iPods for books) are now available, any change in the publishing industry still seems centered on retail considerations, whether in-store or online, as opposed to the aesthetic, monetary, and legal ramifications of a mashup artist such as Girl Talk.

Arguably, all that Girl Talk is doing with music is highlighting the initial creative act and treating it as a finished work, employing what Thomas Mann called “higher cribbing.” In his essay for Harper’s Magazine, “The Ecstasy of Influence: A plagiarism,” novelist Jonatham Letham writes, “Most artists are brought to their vocation when their own nascent gifts are awakened by the work of a master. That is to say, most artists are converted to art by art itself. Finding one’s voice isn’t just an emptying and purifying oneself of the words of others but an adopting and embracing of filiations, communities, and discourses.” A good part of my initial excitement for this project sprang from the sense garnered from years as a reader, from essay upon academic essay, and from learning how editors do their work that books are made from other books; literature is a cleaned-up text collage that has—and here’s the effort—been developed into whole new piece of art after years of work drawing out a source of inspiration to its logical conclusion.

What Girl Talk has done is remind us of our debt to the history of high-cribbing, aided by digital technology that allows him to create and disseminate his sound collages with ease. “What if we did that with text?” I asked myself.

Click for large version

Fast-forward to two weeks ago. It was Saturday around noon and I was preparing for the second day of our weekend-long cut-and-paste party by taping the fruits of the past night’s endeavors to the wall when I realized that this is what it must feel like to be a kindergarten teacher. The day before, I had bought all the materials and lugged into the office a laundry bag full of story confetti I had pre-cut over the course of the week.

Twelve books—a dash of Margaret Atwood for dry wit, a pinch of Dionne Brand to evoke the demographics of Toronto today, some gee-whiz stories about the city’s history to provide historiographic material (the full list of books is here)—reduced to three-line units to be further sliced and diced as the writers (meaning anyone who cared to take part) saw fit.

The choice to cut the pages down to three lines had been difficult. I realized fairly soon after selecting the books (oh-so-scientifically at the UC and Trin book sales based on what I thought would work well together) that the major difficulty with the project would be to provide enough chaos to ensure participants would be forced to be creative, but to also rein it in to the extent that participants would not feel paralyzed with choice. Breaking down the books word by word would not only be painstaking, it would also remove the inspirational element. Sure, I like “legerdemain” as much as the next word nerd, but it’s nothing compared to the mashup sentence “I’m fucked in every kind of way, not least of which was legerdemain.” Equally, a full page of text uninterrupted leaves few opportunities for the imagination to jump in. I was aiming for suggestibility: just enough meaning to tell a story, but not too much.

I was reminded of kindergarten for another reason, and not because I had to remind people to put the caps back on the glue when they were done. I was taping the artworks to the wall for all to see, partly out of wanting to share the beautiful things people created (a full slideshow is included at the end of this article), partly as bulwark against the inevitable question I knew was coming as soon as we sat down to a table covered in what looked like slips from giant fortune cookies.

“So how do we do this?”

The only honest response to which was “I don’t really know?”

With that, we began.

Common knowledge would have it that there are some people in this world who are creative, whereas the rest of us lack the ability. Watching the writers—normal people—hunker down into the quiet of concentration as we reached for narrative, a story—any story—did a lot to dispel this myth for me.

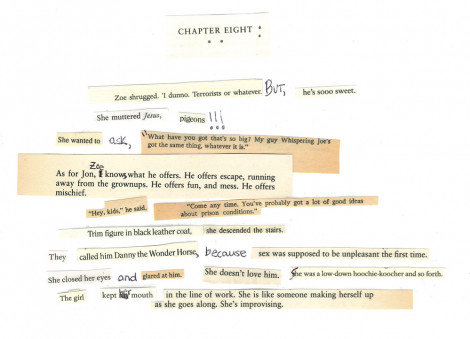

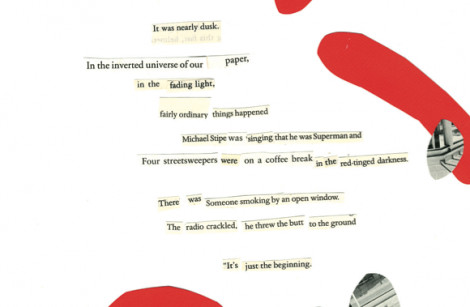

As Lethem noted in his article, collage is a process by which the surrealists attempted to reanimate objects whose intensity had been dulled by everyday use, “an expression of the belief that simply placing objects in an unexpected context reinvigorates their mysterious qualities.” We saw this again and again in the Varsity cut-and-paste project.

I don’t know, said the girl, I pickpocket. I mostly concentrate on the downtown but everywhere I can get to, really.

‘That’s good, that’s great. Keep it up.’

‘But I’m on cleaning systems now. It’s a lot better.

And without much thought he leaned down and kissed her forehead. She looked down and shook her head, and didn’t speak for a while. ‘I guess I should go,’ she said at last.

They looked for all the world as if they were engrossed in some very important conversation.

But let’s be fair, rarely would they cross the path of the public world. They don’t think they had anything at all in common of their own lives.

‘Thank you,’ said the woman, her eyes filling again with tears. ‘It’s very kind of you to come to talk to me. God bless you. Good luck!’

———

Elizabeth Wood shared her husband’s love of the Canadian northland in Don Mills with shaved skulls hooked up to electrodes, rabbits with their eyes mutilated in cosmetics product tests—or slaughtered seals, beluga whales dying in the CANADIAN SPACE PROGRAM on King Street.

———

The pencil was not very sharp, but he outlined a bra of meaning, secretly connected at some deep level he could almost, almost grasp.

The question “How do we do this?” is a lot like the question you may have received from a pre-schooler: “How do you draw a person?” There are some good stand-bys you can use in such an instance—“Well, your person might want a second leg”—but when it comes down to it, you can’t draw a person without taking a stab at it. We’ve all been through this. “Human beings are creative by nature,” Margaret Atwood wrote in September 2008 in response to the Harper government’s slashing federal arts funding. “To be creative is ‘ordinary.’ It is an age-long and normal human characteristic: All children are born creative.” Somewhere along the line, though, someone tells us this is an innate human capacity we don’t have. We should start calling people out on this lie.

There is an alternative ideal to the professional creator, an alternative that may find its epoch in the digital age, with which we may arm ourselves: the amateur. As the novelist Michael Chabon, author of such books as Wonder Boys and The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, explained in his essay “The Amateur Family” (originally published in Details, since reprinted in his new book, Manhood for Amateurs):

Perhaps there is no perfect word for the kind of people I have raised my children to be: a word that encompasses obsessive scholarship, passionate curiosity, curatorial tenderness, and an irrepressible desire to join in the game, to inhabit in some manner—through writing, drawing, dressing up, or endless conversational riffing and Talmudic debate—the world of the endlessly inviting, endlessly inhabitable work of popular art.

When I started in on this project, I knew that there were some questions I’d be able to answer and some I couldn’t. I tried to prepare for both. Nevertheless, I was completely unprepared for the final question as the artists gathered their coats to leave: “Can I take it home?”

Thanks

Tom Bugajski, Jessica Denyer, The Gargoyle, Emily Kellogg, Lola Landekic

Participants

Wyndham Bettencourt-McCarthy, Tom Cardoso, Jade Colbert, Joey Coleman, Jessica Denyer, Cristina Diaz-Borda, Helene Goderis, Alix Gould, Joe Howell, Daniel Kaell, Lola Landekic, Blerta Meraj, Bora Meraj, Ben Nieuwland, Alex Nursall, Sara Quinn, Dan Rios, Esq., Gentleman Will Sloan, Emily Sommers, Erene Stergiopoulos, Diego Laserbeam Valderrama, Shoshana Wasser