University of Toronto department of ecology and evolutionary biology PhD candidate, Janice Ting and University of Maryland researcher and professor, Eric Haag recently co-authored a study, published in the journal PLOS Biology which shows that “inter-species mating between Caenorhabditis nematodes sterilizes maternal individuals.”

PhD student, Janice Ting and U of T researcher and professor, Dr. Asher Cutter in the lab. PHOTO COURTESY OF U OF T NEWS

Antagonistic co-evolution is a well-studied phenomenon in the field of evolutionary biology. Due to the opposing evolutionary interests of males and females, sexual conflict occurs as the two sexes evolve superior sexual traits together to win what scientists sometimes refer to as an evolutionary arms race.

While traits that are responsible for such conflict are usually thought to be outwardly visible, U of T evolutionary biologist and one of the authors of the study, Dr. Asher Cutter said, “This is really the first example that has been shown where the sperm cells themselves are the cause of such problems.”

He specified that for instance, the components of the seminal fluid can sometimes manipulate the physiology of a female mating partner, providing the male with an evolutionary advantage. However the study shows that the sperm cells themselves can cause harm to female partners, sterilizing — if not killing — the females.

“[Hermaphrodites] are able to make offspring by themselves without mating at all,” said Cutter. “A single hermaphrodite individual could have about 300 offspring but what we found is if that she had mated to a male of a different species, oftentimes she would barely lay any offspring at all, so she wouldn’t even use her own gametes in reproduction, she would be effectively sterilized,” he explained.

This occurrence exemplifies the phenomenon of reproductive isolation, wherein a series of mechanisms prevent inter-species mating to mitigate the production of sterile offspring. Therefore, nematodes are incentivized to limit themselves to mating with those of their own species.

The researchers used several different approaches to study these phenomena.

At first, they simply allowed males and females of different species to mate with each other in petri dishes and counted the number of offspring the females were able to produce.

The second approach the scientists decided to try was to use the transparent cuticle of the Caenorhabditis nematodes to their advantage. “We used a trick that is a neat feature of these organisms in that they’re transparent, so what we could do was actually stain the sperm cells of males [with fluorescent dye],” said Cutter, “so that when they mated to a female or hermaphrodite individual, we could observe through the female’s body, how the sperm cells were moving in live animals.”

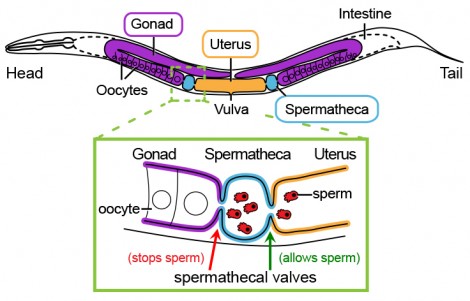

Illustration showing the anatomy of a Caenorhabditis female/hermaphrodite worm. Sperm crawl from the uterus to the site of fertilization (spermatheca). The spermathecal valve prevents sperm from crawling into the gonad, but allows eggs (oocytes) to move into the spermatheca to be fertilized. COURTESY OF JANICE TING

On following the path of fluorescent dye in the female after mating, the researchers noted something extraordinary. “We observed the mated females under a microscope and by using a fluorescent stain to visualize sperm in live worms, we discovered that the foreign sperm had broken through the sphincter of the worm’s uterus and invaded the ovaries,” Ting told U of T News. It is in the ovaries that the sperm fertilized the eggs prematurely, preventing the development of viable offspring, destroying the ovaries and effectively sterilizing the individual.

“In some extreme cases, [the sperm] were able to pierce through the reproductive tract altogether and move around the body cavity of these animals which we think leads to premature death of the individuals,” said Cutter.

Researchers are not sure as to what degree males and females of different species are able to distinguish each other prior to mating. Cutter said, “In the lab, [the worms] quite readily and promiscuously mate between different species, although we have some initial experiments that show that at least in some cases females do seem to avoid mating attempts by males of different species.”

There are a number of different directions in which future research could head.

In terms of genetics, researchers still do not completely understand the genetic causes of what makes the sperm of different male species more or less harmful, in addition to the genetic causes that make females of different species more or less susceptible to harm. Cutter said that it is important to understand these causes, as numerous chemical components that disrupt cellular attraction and cell signaling are fundamental in many organisms.

Another important route is the omnipresent cancer — certain aspects of the manner in which sperm cells pierce through the reproductive tract, are analogous to metastasis in cancer.

Cutter is interested in the genetic basis of these differences to further understand how the genes, traits, and the DNA of nematodes has changed over time in addition to the way in which natural selection and sexual selection have led to such divergence between species.

“Our hope is that by sort of demonstrating this effect that people will be able to look more carefully in other systems to see if similar things could be going on,” Cutter concluded.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Gavin Woodruff was the professor with whom Janice Ting collaborated.