ROM

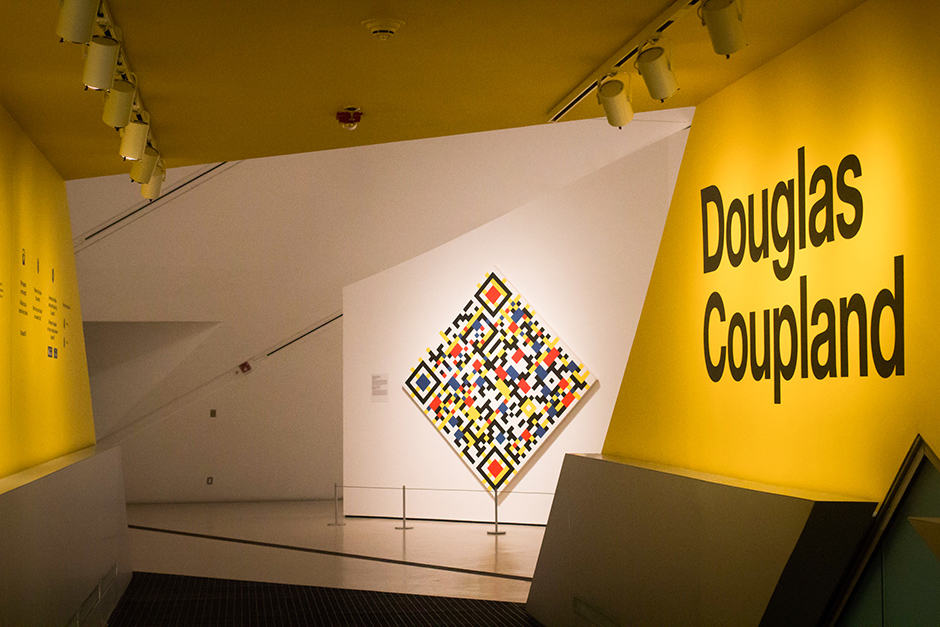

As I walked into the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) last Tuesday afternoon I saw a girl, too young to understand museum protocol, run hands-first into the Douglas Coupland; Everywhere is Anywhere is Anything is Everything exhibition.

Luckily, security was pretty lenient, and it was surely a sight Coupland himself would be proud to see.

The exhibit, much like Coupland’s career, covers popular art, interactivity, and public space in the Internet age. Though the ROM portion of the exhibit is small in size, it is formidable in its depiction of pressing social issues brought about by our engagement with an increasingly digital world.

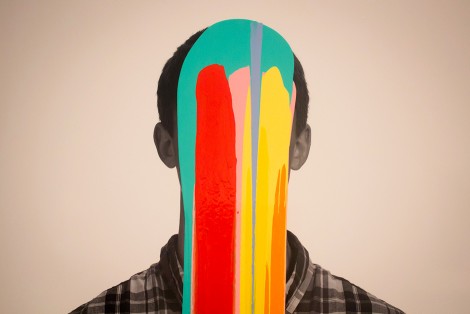

The exhibit explores the inter-relations of people living with and communicating to one another in a virtual and online world. Coupland himself has said in interviews that he doesn’t “really remember his pre-internet brain.” The installations present in the ROM play on the idea of artificial intelligence and the homogenization of thought in a realm of anonymity. What is the distinction between a post- and pre-Internet brain?

The exhibit explores the inter-relations of people living with and communicating to one another in a virtual and online world. Coupland himself has said in interviews that he doesn’t “really remember his pre-internet brain.” The installations present in the ROM play on the idea of artificial intelligence and the homogenization of thought in a realm of anonymity. What is the distinction between a post- and pre-Internet brain?

One example of this mode of thought is the exhibit’s incorporation of smartphones — Coupland’s large QR code paintings in the style of Piet Mondrian provide a description of themselves when scanned by a phone.

A giant wall has been built out of a combination of snarky, sarcastic, and often insightful tweets. This towers over two white buildings that seem to depict New York City’s former World Trade Center. Often the exhibit’s installations pit idea against idea, surrounding the viewer with pieces that interact with each other on an ideological level.

Whether this is the choice of the curator or Coupland, it provides an interesting experience for the spectator. In a sense, the art mimics the state of tragedies overshadowed by a wall of contradicting thoughts and opinions.

MOCCA

Pedestrians making their way down Queen Street West hoping for a glimpse of the newest Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (MOCCA) exhibit will find themselves disappointed — the glass doors to the gallery’s main exhibit hall are swathed in black. You have to venture inside to see the second half of Coupland’s exhibit.

Once inside the mysteriously wrapped space, you are met with a looming gray wall lined with dozens of shelves, featuring the smallest pieces of toy sets — Lego, duplo, wooden pieces — all are fair game. It’s an image that takes a minute to fully process and one that immediately immerses you in the world Coupland has created.

The exhibit makes the interplay of themes at work instantly clear; it manages to be playful and inviting, yet somehow threatening in its immensity.

Turning the corner feels like stepping into an all-Canadian living room. One piece of furniture, the Trans Canada Hutch, is so aptly named that I can’t help but laugh out loud. The chest is decorated with a pattern of highways signs, with the front proclaiming remaining kilometers to destinations like Nipigon, Thunder Bay, and Dryden.

The wall at the far end of the living room is covered with truly Canadian pieces: hockey masks, a small polar bear, a Saskatchewan license plate, a container of Kraft Dinner, an empty gasoline container, and a Crown Royal bag all make an appearance.

The next room features a utopian urban jungle display entitled Towers, made up entirely of crowd-sourced Lego towers — adults and children came together to build them in response to specific key words. It’s colourful and surreal; when I tried to photograph it, it appeared on my screen like a graphic screensaver from Windows 98.

The last room of the exhibit veers back to the theme of Canadian identity, but is comprised mostly of paintings — computerized landscape abstractions that force the viewer to step back and take them in. These works are not about detail, but instead the vast beauty that is the Canadian landscape.

In the center of the room, a mock electrical tower appears to have melted, its top half wilted and lying on the floor by its side. Titled The Ice Storm, the piece pays homage to the 1998 storm that destroyed much of eastern Canada’s electrical infrastructure.

The exhibit showcases the best of Coupland’s work — using everyday objects to create cultural iconography. At first glance, the name of the collection seems to mean nothing at all. After walking through Coupland’s collection, it is clear that it means everything.