We’ve certainly had an interesting few weeks in Toronto. Rob Ford has turned our proper and polite city on its head, introducing a scandalous cast of crack dealers, gang members, and potential prostitutes into the salacious drama that our municipal politics has become. To put it in Mad Men terms, Toronto has gone from Jackie to Marilyn — and if it were television, rather than real life, I’d say I like it this hot.

Every day, there are Toronto Star and The Globe and Mail authors hailing the end of Ford as fanatically as Harold Camping preaches the Second Coming. They denounce him as “brazen and dishonest,” “shocking and embarrassing,” and a disgrace to the city.

But let’s drop the rhetoric and be reasonable for a moment. Is it really Ford’s fault that he’s a fatuous drunkard? Probably. Is it his fault that he’s a racist crack head? Almost definitely. But enough of this was obvious before he ever came into office. How can we blame him for continuing to be exactly the man he was before we elected him with a whopping 47 per cent of the vote?

When it comes to Rob Ford, the buck stops with the voters. The question we need to ask isn’t how we can get rid of the mayor, but how the hell we elected him in the first place. Thankfully, it is a question with an answer: Mike Harris.

In 1998, Harris’s PC government proposed merging the old city of Toronto with five adjacent suburbs. The move was met with stunning opposition — referendums held in the regions opposed amalgamation three to one. Yet, flying in the face of democracy, Harris forcibly created the uncomfortable and incoherent sprawl we now call Toronto.

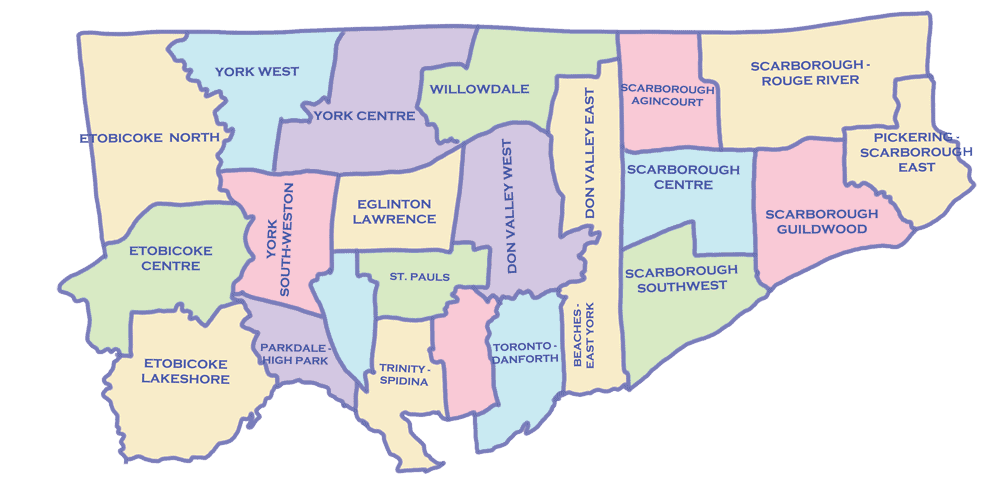

If we look at the 2010 mayoral election results, the wards that voted Ford and the wards that voted Smitherman are divided almost exactly between the city and the suburbs. Simply, the old city said Smitherman, but the megacity said Ford.

The 2010 election is a perfect, microcosmic representation of the reality of modern Toronto: two distinct ideologies, one suburban and the other metropolitan, warring for dominance of the city. In handing the political majority to Etobicoke, Scarborough, and North York, we’ve given the suburban creed a serious advantage in that battle.

Admittedly, we need to get rid of Ford. It isn’t right to have such a man at the helm of our city. But our basic problem is much, much larger than him — and that’s saying something. Ford might leave the mayor’s office, but the people who elected him aren’t going away. Like it or not, they’re not going to vote any more rationally than they did when they called themselves Ford Nation.

The real problem is not Rob Ford, but the simple fact that the suburbs control the downtown core. Some have called for de-amalgamation as the answer — a nice idea, but probably unrealistic. The cost makes the idea politically unattractive, and somehow I don’t think Toronto wants to sacrifice its prestigious title as North America’s fourth largest metropolis.

Realistically, our best chance is to adapt to the circumstances — to stand strong as a city behind a single progressive candidate. Even if Ford were to win 47 per cent of the vote again, 53 per cent is still up for grabs. It is by no means a perfect solution — Ford Nation is an intimidating beast. But in the jumbled reality that is Toronto, it’s just about the only hope we’ve got.

Devyn Noonan is a third-year English student.